At the end of 1918 Germany seemed on the brink of revolution, with violence on the streets and major cities being run by workers' committees. The government maintained order by means of Freikorps - paramilitary groups formed from ex-soldiers and paid through the Army. Some of them chose to paint swastikas on their helmets and vehicles to show who they were.

German stamp (1899-1918)

Stamp from the Weimar Republic (1919)

Yet the revolutionaries did not sweep to power in the German elections of 1919. Most people voted for parties of the right and the centre. The resulting coalition centre-right government felt Berlin was unsafe, so the new parliament met at the country town of Weimar, 150 miles to the south. I've written here on the origins of the Weimar Republic.

For the past twenty years Germans had grown used to sticking pictures of Germania on their letters. This image (top left) was supposed to symbolise the German nation in some way, as Britannia did on British pennies. But the authorities took care to add Deutsches Reich (German Empire!) underneath to make clear which nation was being symbolised. The British authorities, of course, didn't bother to identify their country on their stamps. For them there were only two kinds of stamps - British, showing a portrait of the monarch, and others. Foreigners had to put their country name on their stamps to show they weren't British.

The first stamps issued by the new German National Assembly appeared in July 1919. At first glance the design shows a stylised bricklayer with a vaguely Egyptian air.

But on closer inspection all those right-angles begin to suggest something else, and it seems suddenly clear that the designer has actually drawn two things at once. The image is both a bricklayer and a swastika.

Or perhaps this is just coincidence. If it's not, it suggests that the designer was instructed by senior people in government to quietly spread the idea that the swastika was now an important national symbol.

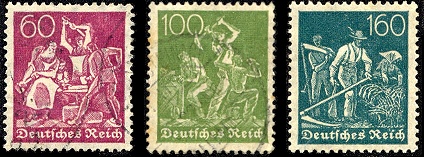

The next new design came in 1920. Some values displayed posthorns, whilst others showed no more than the price paid for the stamp. But three designs illustrated labourers. There were blacksmiths, miners, and farm workers.

The next new design came in 1920. Some values displayed posthorns, whilst others showed no more than the price paid for the stamp. But three designs illustrated labourers. There were blacksmiths, miners, and farm workers.

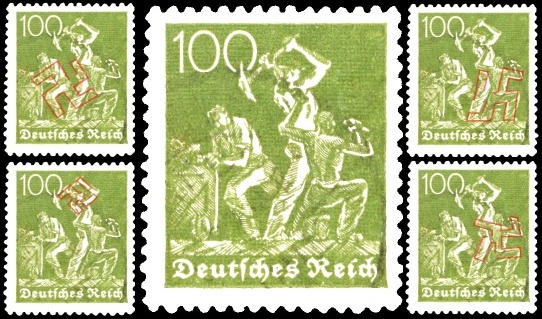

The green 100 pfennig stamp illustrating the miners also seems to contain several right-angles. I wondered if the slightly odd poses were supposed to indicate that this image too was carrying a hidden message, so I looked for a swastika in the design. I found four! The two on the right (above) may owe some debt to the eye of faith, but the two on the left seem strikingly clear.

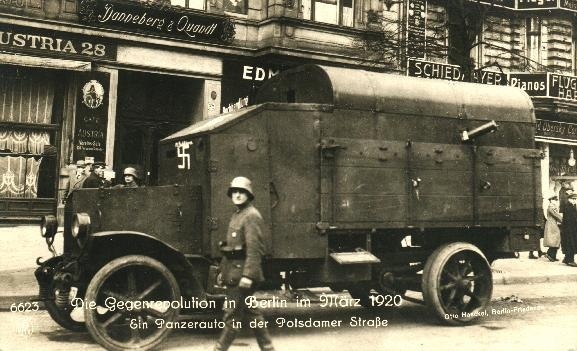

1920 was the year of the Kapp putsch, when Freikorps units occupied Berlin in a bid to overthrow the politicians running the Weimar Republic. The Treaty of Versailles compelled Germany to reduce the size of its massive Army, and it must have seemed logical to begin by disbanding the Freikorps. The Marinebrigade Erhardt, which had been the first Freikorps unit to begin using the swastika symbol, took strong exception to this move.

Normally, the Army would have been called in to put down the insurrection, but in this case the Army flatly refused to cooperate. In desperation, the government called for a general strike, and the workers supported the government. Kapp tried, and failed, to form his own government, and the strike paralysed the country. Kapp and his fellow conspirators fled.

There is one more twist to this story. In 1922, a couple of years after the abortive putsch, inflation was becoming a serious problem and new values of stamp were urgently required. The postal authorities responded by re-issuing (in different colours and values) the designs showing farm workers and miners. But this time, the miners design only was changed so that it became a mirror-image of the previous stamp. The 100 pf green becomes 20 Mark purple (below), and the swastikas - if that's really what they are - now have the orientation decreed as correct by a rising young politician named Adolf Hitler.

If the symbols are really there, and were meant to be noticed, then there must have been some not-too-well concealed support by the right - the monarchists, the landowners, the Army - as early as 1918 for the swastika as a national symbol to help unify the country. Overt publicity of the swastika would have aligned the government with the paramilitary Freikorps, whose aims were not the same as government's, but tacit support must have been considered necessary. So when Hitler announced in 1920 (say some sources, but I can't confirm this) that the NSP symbol would be the Hakenkreuz, he was really tapping into a deep national feeling of all that the symbol now represented. And this feeling had been present since the end of the war.

Or I suppose you could argue the opposite - that the Weimar government was in fact deeply opposed to the philosophy of the NSP, but that some powerful elements within the state felt able to use the inoffensive mechanism of the postal service to express their own support for the NSP's "pure" nationalism, and did so by hiding the swastika in the images.

I'm not totally convinced by the hidden swastikas, but it does all seem just a bit odd ...

Footnote ...

In 1918, Bill Lambert was flying an SE5 fighter over France as a member of 24 Squadron. His book Combat Report includes a couple of photographs of captured German aircraft.

Swastikas are clearly visible on both. What's more, the Pfalz (on the right) has been repainted and now has a French roundel. Were the French using the swastika too? Was the symbol no more than a good luck charm - a sort of rabbit's foot? Or was something else going on?