This essay analyses birth rate and marriage data in 19thC Swaledale. It is one of a series of essays about the people and communities of Swaledale.

Family sizes and birth rate

We have all seen photographs of Victorian families with their many children sitting solemnly on mother's knee, or clustered around, aged apparently 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9 and upwards. There were certainly a lot more children around as a proportion of the total population. I counted how many children had been born in Swaledale between each census.

| children aged 10 and under | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 |

| total number of children | 2098 | 2145 | 1846 | 1468 | 1321 | 769 | 547 |

| % of population | 31% | 31% | 30% | 27% | 28% | 24% | 21% |

In 1851 children under 11 were 31% of the population of England. In 2008, 31% of the population was under 25, not under 11.

For comparison, Birmingham (UK) Council's summary of its city's results from the 2001 census gives one useful fact: 31% is now the proportion of England's population aged under 25, not the proportion aged under 11 (as it had been in 1851).

So I calculated average family size in 19thC Swaledale with some anticipation, and was disappointed to find that it was 5 in 1851, 1861, 1881 and 4 in 1871, 1891 and 1901. I thought it would be much higher, then realised I would have to be more selective and exclude those households which did not have any children at all.

The largest dale population occurred in 1851, when the total number of residents was 6,835. Of these, 1,936 (29%) were under the age of 10. So I extracted all those 1851 Swaledale families with at least one child under the age of 10. In the few households which had grandchildren (and nieces and nephews) mixed in I chose not to try to find their originating parents; I simply excluded the households from the analysis.

Of the total number of households in Swaledale in 1851 (1,417) only 20% did not have young children. In this chart the pale area represent those families with young children. For comparison, the Family Studies Policy Centre report published in 1995 shows the opposite (in the UK) – the dark area would now almost represent households with dependent children.

And of the families with young children, the family size was as follows:

| No. of children | No. of families | Mother's age (avg) |

| 11 | 1 | 41.0 |

| 10 | 5 | 40.8 |

| 9 | 8 | 42.4 |

| 8 | 16 | 43.4 |

| 7 | 39 | 39.5 |

| 6 | 63 | 40.2 |

| 5 | 88 | 39.3 |

| 4 | 130 | 36.5 |

| 3 | 152 | 34.8 |

| 2 | 140 | 31.4 |

| 1 | 103 | 28.0 |

The third column in the table above shows the average age, in 1851, of the mothers of each family size. I expected the 1- and 2-child families to have mothers much younger, in line with the Age at Marriage graph below. The difference is that some women had their first babies in their 30s. Even so, you can see that the mothers of small families had years of child-bearing ahead of them.

A three-year gap in the family usually meant that a child had died

Many of these families will, in addition, have had children who died. A 3-year gap or more between regularly-spaced children suggests a death, even when the baby has been born and died between censuses and the only other record is in parish registers. I did make a diversion to look at this, and made a list of all the infant and child deaths recorded in the parish registers within Swaledale between 1638 and 1901. I have a list of 8,500 names. In principle I could cross-check every name against the baptism registers and calculate how old each child was when she or he died. Then I realised that of the 8,500 names, over 1,000 were called ALDERSON, and I reluctantly abandoned the idea. But I still have the lists, just in case.

Here is that 11-children family in 1851:

| Thomas | Elizabeth | Jane | Elizabeth (maid) | Thomas | John | Ralph | Mary Martha | James | Ann | Charles | William | Hannah | George |

| Head | wife | dau | dau | son | son | son | dau | son | dau | son | son | dau | son |

| M | M | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 51 | 41 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3m |

The 1841 census shows that Thomas and Elizabeth had another daughter, Elizabeth, then about five years old, but since she does not appear with them in 1851 I thought she must have died. However, a quick check in the complete Swaledale census list showed her working for the landowning Harland household in 1851 as one of three domestic servants. I later found yet another daughter - Catherine - farmed out to her grandparents.

So in fact the biggest family in the dale had 12 children, not 11. And all of them must have survived because there is just not a big enough gap in the ages to fit in one more. The family’s 70-acre farm had a lot of work to do. And there was a loose 8-year-old called Matthew living with (aunt?) Margaret in Reeth. A 13th child from the family? But there were two other Nelson families in the dale with young children, so I stopped here. You can get too obsessive.

Elizabeth was 41 when George was born. I could not bear the thought of her having more babies so I tracked her down. In 1861 she was living with her husband Thomas Nelson, a cowman in Gilling, Richmond, with their children James, Ann and George. George was their youngest. Catherine, yet another daughter, who had been with her Blenkiron grandparents since at least 1841, was still with them in 1861 in Marrick. Her existence made a total of thirteen children, and there they all are in the Marrick baptism register.

Eight children in the NELSON family died of cholera; George and Elizabeth moved the rest away

Footnote: A year or so after this essay was published on our website I went on to look at parish register BMD transcripts, and was horrified to find that several of these children died in the same month in 1853. They had indeed all survived to be in the 1851 census, but a cholera outbreak in May took the lives of Hannah (4), William (6), Charles (7), Mary (12), Ralph (13), John (14), Thomas (16), and Jane (18). Eight of them. Can you imagine it? No wonder the parents moved the rest of their family away.

Slater's 1849 Directory of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire reports that at Reeth's November Cattle Fair (a big bi-annual event) prizes were awarded for the best cattle and sheep, and to industrious miners and labourers who had brought up large families. So that's the explanation.

Age at marriage

Of the 187 wives under 30 in the 1851 young family data set I have been working on, and assuming no earlier miscarriages or stillbirths (an unknown quantity), the following graph shows how old each young mother was when her first child was born.

It is fairly safe to assume that babies quickly followed any marriage so the graph also gives a reasonable distribution of age at marriage if you deduct 1 year from the labels on the x axis.

It seems that most marriages took place when the women were between 20 and 22. But given how common it is in the 20thC for a first pregnancy to end in an early miscarriage, maybe that estimate should be reduced by another year.

For comparison, the British Office of National Statistics say that in 1999 the average age for first marriages was 28 for women and 30 for men.

Death in childbirth

Of the widowed parents in the 1851 census, 46 were widows and 32 were widowers, which suggests that childbirth was almost as dangerous as lead-mining. My great-grandfather, and my great-great-grandfather, found themselves in this unhappy position and I have added their story at the end of this essay.

Twins

I could find only three instances of young twins in the whole dale in 1851, and in each case the family already had at least 6 children. My heart sinks at the thought of it.

Illegitimacy

The censuses record a number of unmarried women with one child, sometimes more than one. In 1851 there were 23 apparently illegitimate children, though the word “illegitimate” only occurs once in the whole set of Swaledale census lists for 1841-1901!

Of the 1,417 Swaledale households in 1851, just 13 were run by single unmarried women with children. A further 11 included unmarried daughters with an acknowledged child (that is, the baby was shown as the householders’ grand-child).

Some accidental babies were absorbed into the household with little fuss

I have read of couples who said their grandchild was their own son or daughter, to protect their unmarried daughter’s reputation. How likely is this? Of the family households, maybe 16 (0.01%) had a daughter still living at home and old enough to be the mother of one of the babies assigned to her parents. My reasoning was that if there was a regular string of evenly-spaced children, and then an age gap between the youngest and the next-youngest, it suggests that the mother had stopped having babies and her oldest daughter had started. It was also a clue if the mother was in her 50s. Here is an example:

| John | Isabella | Elizabeth | John | Metcalf | Adam |

| Head | wife | step-dau | son | son | son |

| M | M | U | - | - | - |

| 38 | 42 | 19 | 12 | 9 | 1 |

Even more telling is that although Elizabeth retained her father’s surname, Adam was given John and Isabella’s surname in the census.

There was the possibility than an unmarried son had an illegitimate child living with his family, given the level of deaths from childbirth. I made a brief diversion into the Burial registers and found some significant coincidences between deaths of young unmarried women and adjacent deaths of infants. I actually found a couple of maternal deaths where it was very clear that a nearby young man's family had acquired a new baby in the household, but this kind of research can sometimes make people uncomfortable so I decided not to go further. However, the baptism names of some of the babies were occasionally a clear indication of the name of the father. The local clergy could be downright cruel - there is one story about a clergyman who insisted in recording a young man's original baptism surname (his mother's) in the marriage register, even though everyone knew that the boy's father had acknowledged him, had later married the boy's mother and in fact brought him up, and he had always been called by his father's surname. The law is the law, said the clergyman. Pompous bigot.

I would be interested to learn more about contemporary attitudes to illegitimacy.

Contraception

We know now that nutrition levels affect fertility, and that the menarche is later in girls who are poorly fed. I have noticed only a few teenage pregnancies in the Swaledale data but when searching for absent spouses and a marriage date I quickly learned to check the GRO Marriage Index right up to just before the first baby’s birth.

It is clear that once a couple started having babies, they would continue for many years with alarming two-yearly regularity. I suspect that the occasional gap marks a child who died, rather than a six-month headache, but what did the women do for contraception? Abortion, infanticide or abandoning the baby must have happened occasionally. Rubber condoms became available in the 1840s, replacing those made from animal guts (the Open University website has a photograph of a condom to be secured by a red silk ribbon!) but diaphragms did not become available until the 1880s. Acidic lemon juice was known for centuries to be an effective spermicide for sponge or douche but there are not many lemon trees in Swaledale. Maybe the local grocers (or their wives) obtained a steady supply and everyone said how much they enjoyed lemon tea.

Second marriages

An age gap in children, and an age difference in the parents, suggests a second marriage, like this:

| Joseph | Ann | John | Joseph | Mary |

| Head | wife | son | son | dau |

| M | M | - | - | - |

| 50 | 28 | 13 | 10 | 1 |

In 1851, about 5% of Swaledale's marriages were second marriages. In Britain today the re-marriage rate is closer to 25%.

Twenty-two families in 1851 recorded the presence of step-children, which means that 22 widows had married again. But of course if a widower re-married all children would be counted as his sons and daughters (not his step-children), so it is difficult to establish how many second marriages there were altogether. Most married couples were the same age, or within 3-4 years of each other so, looking down the complete 1851 list for Swaledale for age gaps between parents and between children, and whether the wife was old enough to have borne the oldest child, I would say there were about 40 families where a widowered father had re-married. This gives a total of 66 second marriages for the dale, or about 5%. So almost twice as many widowed fathers re-married than widowed mothers, again illustrating the dangers of childbirth. Today, in Britain, the re-marriage rate is nearer 1 in 4.

But I remind myself that for many couples re-marriage was as much necessity as choice. Housing was very limited, work for women was very limited, and the reciprocal care and affection available to widows and widowers must have persuaded many to take on each other's children as well as each other.

This is just what happened in my own family, and it involved Ann BUXTON of Gunnerside. I have written about her, and here second marriage, elsewhere on this website, but she is exactly the type of young woman who solved the problem faced by a young widower whose wife died before he would have chosen. I don't have any photographs of the early family, but I do have a number of funeral cards, and memorial inscriptions. Which is a sign of the times too.

Two young widowers in my own family

In 1868, my great-grandfather Isaac WINTER married Ann SPENCELEY, the daughter of Coverdale gamekeeper James SPENCELEY and his third wife Jane METCALFE of Ivelet Heads.

That was going to be how I started this final section, but I realise instantly that the story goes back a generation, and for similar reasons. Because James SPENCELEY's first wife - Mary FALSHAW - died in September 1830 aged just 21. Their marriage had taken place in April 1829 and their daughter Margaret had been baptised on 14th May 1830. I don't know Margaret's date of birth, and it was well before the civil registration of births was introduced in 1837, so I can't say for certain that Mary died of puerperal fever - childbed fever as it was called then - but it does looks likely. Poor James, a widower at 30, was left with a baby daughter and a busy and demanding job. He was gamekeeper to Sir William Chaytor and the grouse season of 1830 would have been well under way at the butts just along the ridge from his cottage. There were FALSHAWs at the neighbouring farm at Ings, so it is possible that Mary was their daughter, and that there was immediate and local help for James.

But he needed a longer-term solution and in April 1832 he married Elizabeth GRAHAM, of Askrigg. Their daughter - Rosamond - was baptised in September 1834. Elizabeth died in November 1836, so James was a widower again, now with two small daughters. All this time he was living at Widdimans, up on the top of Caldbergh Moor. His house - seen as a ruin by a member of the Upper Dales FHG when she used to walk her dog - was very simple: two downstairs rooms, one with a chimney, and an open ladder-staircase up to rooms in the loft. There was spring-water nearby, and that was it. To this house James SPENCELEY brought his third wife - Jane METCALFE (b 1806) of Ivelet Heads - in May 1938. They lived there for thirty more years and had four more children - one of whom died as a child. Now the moorland around Widdimans just has a few stones and this door latch to show where one family had lived for over forty years.

Their surviving daughter was called Ann, and as a teenager she went into service at Borrenthwaite Hall on Stainmore, where the neighbouring farm was being run by her mother's sister Rosamond COATES. And that is how Ann met Isaac WINTER of Calva House. There - I am back where I started.

Isaac and Ann (Spenceley) WINTER had seven children at the family home of Calva House:

- William Wilson b 1869

- James Spenceley b 1871 (on a visit to Ann's parents briefly in Barnsley)

- Mary b 1873

- John Francis b 1875

- Annie b 1876

- Isaac b 1878

- Rosamond b 1880

By 1881, James and Jane SPENCELEY had finally retired and moved to Calva House to live. Isaac's own father was still alive and running the 65-acre farm with the help of Isaac's sister Elizabeth and a couple of farm servants, so the extended family household contained three generations. Isaac was working for the railway company - the new line had been put across Stainmore at great expense in the 1860s - and life must have seemed busy and purposeful and good.

Then, in 1882, Ann died - aged just 32. I wonder if Isaac's mother-in-law Jane did a bit of quiet organising (these METCALFE women were great organisers and their influence shows in many of my family stories), because at the end of 1883 Isaac married Ann BUXTON - his first wife's cousin, and Jane's niece. Ann BUXTON had moved from Gunnerside with her father (Jane's brother-in-law) and two brothers to farm at Bleathgill, just along the moor from Calva House. Ann was aged 34 and probably in need of a permanent home herself, because her father had just died and her brother had recently married. She and Isaac had no more children and when James then Jane SPENCELEY finally died, I suspect it was she who moved the family off Stainmore and down to a very pleasant farm at Otterburn Hall, near Gargrave. But from her later behaviour, and stories told by my uncle, she loved her step-children dearly, and had the sorry task of supporting Isaac as three of his children died in their teens:

- The first to die was Rosamond b 1880 died 1895, aged 15

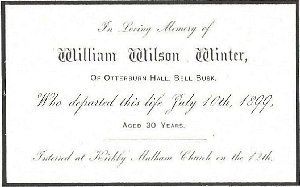

- then, in quick succession, William Wilson b 1869 died 1899, aged 19.

- and Isaac b 1878 died 1899, aged 21

- John Francis b 1875 married and farmed at Otterburn, but died in 1916 aged 40 (my transcript of his obituary is here).

- Of the other children - James Spenceley ( my grandfather) married Hannah DAVIES nee WOOD, of Bradford; Mary married Charles RICKARDS and farmed at Bell Busk; Annie b 1876 married Joseph WHITELL.

Probably after the deaths in 1899 of young Isaac (11th Jan) and then the eldest, William Wilson (10th July), the WINTERs moved out of Otterburn Hall to the neighbouring Kendal House, where their son John Francis started his own farming career.

Isaac WINTER died in 1909. In his will, where he described himself as Yeoman, he left a freehold estate called Sturdy, in the parish of Kaber (I have no idea yet where that came from) and £735 13s 4d to be divided into equal shares for all his surviving children and for Ann, who also got all the furniture. (£735 was roughly equivalent to £300,000 in 2008.) He also had stock and crops on Legrams farm, which he left to John Francis. His executors were John Francis, and James Robert METCALFE took over at Otterburn Hall and was Ann Buxton WINTER's nephew.

Her step-son James Spenceley WINTER and his new wife stayed at Kendal House for a short while, then took a farm at Denholme, up on the moor outside Keighley. Was it a coincidence that Field Head Farm at Denholme was being run by Alexander KILBURN (b Muker) and his wife Isabel (b Ivelet Heads)? Isabel was Ann Buxton WINTER's niece and the granddaughter of Jane (Metcalfe) SPENCELEY's youngest sister Mary Ann. I have come to believe anything of these determined METCALFE women.

When Annie and Joseph WHITELL later moved to live in Scarborough, Ann (Buxton) WINTER sold up and moved there too. She died in 1927, having mentioned every one of her surviving step-children and nieces/nephews in her will.

This story of the SPENCELEYs and WINTERs, with its early deaths and upheavals to move away from sad places, was not unusual, as we have seen earlier with the NELSONs and the awful events at Marrick. Here is a link to the story of the early life of James and Jane SPENCELEY, together with the story of how James Spenceley WINTER met his wife, and the earlier Stainmore story where the METCALFE siblings between them had just about every farm and house in the area.