Rochdale to Halifax in 1725

The writer Daniel Defoe travelled on horseback through England and Wales between 1724 and 1726.

More than a thousand years earlier, the Romans had constructed a network of solidly-made military roads across England to link London with their other main settlements. In Defoe's time they were still the best roads in the country. The postal service used them, so most letters were routed via London. However, due to the volume of correspondence generated in the north and west of the country, the Post-Master General had recently established a cross-post route which ran from Plymouth in the far south-west up through Bristol and Gloucester to Liverpool, and then across via Manchester and Leeds to Hull. Since this route was presumably already a major traffic artery, it would seem reasonable to suppose that it was well maintained and adequate for its purpose. The reality was rather different, as Defoe found when he followed it from Rochdale to Halifax, a ride of about fifteen miles along a main highway of the time, now known as the A58. What follows is taken from his account of the journey, in the summer of 1725.

It was the middle of August, and in some places the harvest had only recently been gathered. Even so, the cold was 'very acute and piercing', and the mountains were covered with snow. There was a little overnight snow on the ground, but the sun was shining as the travellers left Rochdale in the early morning and rode east towards the hills. After a mile or so they were riding uphill, and the wind was beginning to rise, and then it began to snow. By the time they reached the top of the hill the snow was blowing straight into their faces. They had difficulty keeping their eyes open for long, and the track they were following had disappeared under a thick blanket of snow. Even the horses were uneasy, and Defoe's little spaniel turned his back to the wind and howled piteously.

They paused, and debated whether they should return to Rochdale. Then one of the servants, who had ridden a little ahead, called out that he could see Yorkshire on the other side of the hill, and that there was a plain way down. They joined him, and Defoe says that he could see

the mark or face of a road on the side of the hill ... but it was so narrow, and so deep a hollow place on the right, whence the water descending from the hills made a channel at the bottom, and looked as the beginning of a river, that the depth of the precipice and the narrowness of the way look'd horrible to us.

They decided to continue on foot, leading their horses. After about a mile the blizzard had lessened, and eventually they came to a house where they asked their way. There followed another steep descent, again on foot, and when they arrived at the bottom they found 'a few poor houses' where again they could check that they were on the right road.

Defoe continues, rather innocently,

We thought now we were come into a Christian country again, and that our difficulties were over; but we soon found ourselves mistaken in the matter; for we had not gone fifty yards beyond the brook and houses adjacent, but we found the way began to ascend again, and soon after to go up very steep, till in about half a mile we found we had another mountain to ascend, in our apprehension as bad as the first, and before we came to the top of it, we found it began to snow too, as it had done before.

And when they had successfully climbed this 'mountain' and reached the bottom on the other side, there was another one ahead of them, and in the space of eight miles they crossed eight steep hills. They did eventually get to Halifax, but I suspect this was a journey that Defoe would never quite forget.

He was used to the roads being bad (though this didn't stop him complaining about them) and offered the thought that

the soil of all the midland part of England, even from sea to sea, is of a deep stiff clay, or marly kind, and it carries a breadth of near 50 miles at least, in some places much more; nor is it possible to go from London to any part of Britain, north, without crossing this clayey dirty part.

Since the affected counties enjoyed a great deal of trade with London, as well as between themselves, and the routes north lay through them, so

the roads had been plow'd so deep, and materials have been in some places so difficult to be had for repair of the roads, that all the surveyors rates have been able to do nothing; nay, the whole country has not been able to repair them.

It was the responsibility of the local authority, such as it was, to use local resources to keep the roads in its district in good repair. The task was beyond most of them, and they knew it, so they didn't try very hard. Some didn't try at all. Besides, the local people were too concerned with getting their daily bread to worry much about improving the roads - if it took them two hours to get to market instead of one hour, so what?

Blind Jack Metcalfe

Jack Metcalfe was born in 1717 at Knaresborough. He became blind at the age of six following a bout of smallpox, so his parents arranged for him to learn the violin to give him a means of earning his living in later life. He grew into a friendly and convivial man with a ready intelligence. Despite his handicap, he liked to travel, and he walked all over the country. At one stage he set up and ran a business transporting fish from the coastal ports to Leeds and Manchester using packhorses. This was not a man who needed a guide dog to find his way.

Blind Jack must have been an unforgettable character, and several books include affectionate anecdotes about him. When I first came across the story of his walk home from London I was half-inclined to dismiss it as fantasy, but it's so much in keeping with the other adventures in his life that it rings true.

Blind Jack must have been an unforgettable character, and several books include affectionate anecdotes about him. When I first came across the story of his walk home from London I was half-inclined to dismiss it as fantasy, but it's so much in keeping with the other adventures in his life that it rings true.

Defoe earned his living by his writing, and a sceptical person might suspect that he exaggerated the difficulties of his journey in order to make it a better story. He had certainly exaggerated his name - he was born plain Daniel Foe, and added the 'De' to make it it sound better. But in fact, the roads really were awful, as the story of Blind Jack's trip home from London makes clear.

Whilst he was spending some time in London, he met Colonel Liddell, the MP for Berwick on Tweed. Liddell lived at Ravensworth Castle near Newcastle but also had a house in Covent Garden. He was about to journey north, and offered Metcalfe a seat on top of his coach as far as Harrogate. Metcalfe thanked the Colonel, but declined his offer, saying that he could walk as far in a day as he chose to travel. They agreed to meet at an inn each evening.

Both travellers left London around mid-day on the Monday - Liddell in his coach, with sixteen servants on horseback, and Metcalfe on foot - and travelled separately. That evening, when Liddell's party reached Welwyn, about 20 miles away, Metcalfe had already arrived at the inn. After breakfast the next morning both parties set off again, and that evening they met up again. This continued every day until they reached Wetherby on the following Saturday. The 200 mile journey had taken 60 hours. It was literally impossible on these eighteenth century roads to drive a coach faster than a man could walk.

Jack would not have been walking quickly - he was blind, after all - but he must have kept up a steady pace. An attorney's clerk named Foster Powell, whom some called "the Horsforth Pedestrian", walked from London to York and then back again several times between 1773 and 1792, and it usually took him six days to cover the 400 miles.

Incidentally, Blind Jack tried his hand at many things during his long life, including surveying and building sections of turnpike road in Yorkshire and Lancashire - not just the odd few hundred yards, but many stretches of road several miles long, with bridges where they were needed.

His body is buried in Spofforth churchyard, close to ancestors of mine who will certainly have known him.

Packhorse trails

Driving a carriage from London to Wetherby is one thing. It's a different matter to move, say, a ton of lead, across the Yorkshire moors from the smelting works near the pit to the town where the customer wants it. There were no roads across the moors. There were tracks, of course, but they were too steep and rocky for any wheeled vehicle to use. The only viable solution was a string of packhorses. It took around ten of them to carry a ton, and they could move surprisingly quickly,

Driving a carriage from London to Wetherby is one thing. It's a different matter to move, say, a ton of lead, across the Yorkshire moors from the smelting works near the pit to the town where the customer wants it. There were no roads across the moors. There were tracks, of course, but they were too steep and rocky for any wheeled vehicle to use. The only viable solution was a string of packhorses. It took around ten of them to carry a ton, and they could move surprisingly quickly,

especially when their panniers were empty.

especially when their panniers were empty.

Not just lead, but wool, coal, hides, iron and a huge range of manufactured goods were moved around the country by packhorses. Blind Jack Metcalfe used them to transport fish from the coast to the towns. He was just as comfortable travelling by night as in the daytime, and the fish arrived relatively fresh.

Where it was more convenient for the packhorses to use an existing road, it was common practice to make an all-weather track for them along the side, out of the mud. These causeways have survived, here and there, and can still be seen beside roads that have been improved to modern standards but do not justify more major investment, as here in Glaisdale.

As late as 1753 the roads near Leeds consisted of a narrow hollow way little wider than a ditch, barely allowing of the passage of a vehicle drawn in a single line; this deep narrow road being flanked by an elevated causeway covered with flags or boulder stones. When travellers encountered each other on this narrow track, they often tried to wear out each other's patience rather than descend into the dirt alongside. The raw wool and bale goods of the district were nearly all carried along these flagged ways on the backs of single horses.

But when the state of the roads would allow, it was much more efficient to transport the goods by horse-drawn wagon than by packhorse. A team of eight horses could shift the same load as thirty packhorses.

Surveyor of the Highways

A mediaeval 'road' was really just a right of way. Often it was no more than a well-trodden path across open fields and hills. It wasn't surfaced, and it wasn't fenced, and there were almost no signposts, so in the dark or in bad weather it was stupidly easy to get lost. Locals knew the roads, but no-one else did. Cautious travellers employed a guide.

Roads in the eighteenth century (with the exception of the few Roman roads) were just as bad as they had been hundreds of years before. Since it was nobody's job to construct a road - they existed simply because people chose to use that route - the king's highways were bumpy, rutted and full of pot-holes. In summer they were dusty and difficult, but when the weather was bad they could become sticky, impassable swamps. It was generally accepted that wheeled vehicles could not use the roads during the worst four or five months of the year.

Since it was nobody's job to construct a road - they existed simply because people chose to use that route - the king's highways were bumpy, rutted and full of pot-holes. In summer they were dusty and difficult, but when the weather was bad they could become sticky, impassable swamps. It was generally accepted that wheeled vehicles could not use the roads during the worst four or five months of the year.

Central government saw road maintenance as a local government problem.

Each parish was simply commanded to keep its own roads in good repair, and left to get on with it. In mediaeval times it had been normal for every man to spend part of his time working on his lord's land, so delegating responsibility in this way must have seemed the obvious and sensible thing to do.

Each parish was simply commanded to keep its own roads in good repair, and left to get on with it. In mediaeval times it had been normal for every man to spend part of his time working on his lord's land, so delegating responsibility in this way must have seemed the obvious and sensible thing to do.

The rules laid down by government were perfectly fair, in theory. Every man in the parish who owned or occupied land worth £50 a year or more was obliged to supply a cart, horses, tools, and two men for six days to work on the roads. (The obligation was on the tenant, not the landlord.) Everyone else had to give their labour for six days each year, or provide a substitute. The parish council appointed one of their number as 'Surveyor of the Highways' to organise this labour force and direct it to where it was needed. The appointment was unpaid, and lasted for a year.

In practice this meant that the unfortunate individual who was chosen as Surveyor had to persuade the major landowners in the district to spend their own time and money on making good the worst sections of the highways in his care. If they refused, he could in theory arrange for the full majesty of the law to descend on their heads, but these people were his neighbours, and in many cases his friends. He had to live with them afterwards, and it would not have been sensible for him to annoy the leading figures in the community simply to make journey times a little shorter.

In any case, the grandly-titled Surveyor had no more knowledge or experience of road-building than the next man, and no money to spend apart from what he could raise locally. And he knew that in twelve months' time it would be somebody else's problem anyway, so the temptation to do as little as he could get away with must have been close to overwhelming.

Most Surveyors considered that they had done their duty if they rode around the parish two or three times a year. If a section of road seemed particularly bad they might have a word with someone about it, but that was about all. The roads did not improve under this system. They grew steadily worse as the weight of traffic increased, and something had to be done.

Turnpikes

The quality of the road network only began to improve with the coming of the turnpikes, which were gated roads that travellers could only use if they paid a fee. The word 'turnpike' is quite old, and must originally have related to burly men with pikes barring the way to the king's presence. Or possibly not. Either way, 18th century turnpikes used gates to block the road, not weapons.

The idea was that the fees would be used to pay contractors who would build a proper modern road and keep it maintained. Everyone would benefit eventually, and once the road was finished the fees could in principle be reduced to a much lower level, just sufficient to pay for occasional repairs.

The obligation of parishes to continue their contributions towards keeping the road maintained (the so-called Statute Duty) did not stop when the road was turnpiked. Yet despite the obvious objection that the first travellers would be paying out good money to drive on the same bad road, turnpikes were a great success. They were the direct cause of Britain's roads being transformed from uneven muddy swamps into useable highways. In 1754 the journey from London to Manchester took four and a half days, but 30 years later it took just over a day.

The scheme worked like this. First, an aspiring entrepreneur applied to Parliament for permission to improve a section of road. Once Parliament had approved this by passing an Act, the road was effectively privatised for a period of typically 21 years. The new owners were allowed to set up a turnpike at each end of the section and charge all travellers who passed through it. It was a sort of legalised highway robbery.

There was a small but energetic minority who were not prepared to put up with this, which they considered

... a grievous tax upon their freedom of movement from place to place. Armed bodies of men assembled to destroy the turnpikes; and they burnt down the toll-houses and blew up the posts with gunpowder. The resistance was the greatest in Yorkshire, along the line of the Great North Road towards Scotland.

Some people were genuinely outraged that they now had to pay to travel along the public roads, and this was not an age when protest was peaceful. Turnpike riots took place all over the country.

When the first turnpikes near Leeds were opened, the exaction of tolls excited an immense ferment among the people, and they determined to destroy the toll bars and the houses of the collectors. They demolished the gate between Bradford and Leeds, and also those at Halton Dial and Beeston. Three of the rioters were apprehended at the latter place, and conveyed before the borough magistrates then assembled at the King's Arms inn, in Briggate. The mob having in the morning rescued a carter who had been seized by the soldiers for refusing to pay toll at Beeston, assembled before the inn with the determination of liberating the prisoners, and they soon broke the windows and shutters of the house with stones which they tore up from the pavement. The magistrate ordered out a troop of dragoons but the mob furiously assaulted them as they had previously done the constables. Orders having been issued for the closing of the shops and for every family to retire as far as possible from danger, the troops were commanded to fire first with powder and this producing no effect, with ball. The people then fled in all directions, leaving in the streets about ten persons killed and 27 wounded. Some of the latter afterwards died, and many others were injured.

Defoe found no-one who complained at the tolls (in his day, typically 1d. for a horse, 3d. for a carriage, 6d. for a cart) but I suspect he didn't ask many local farmers. They were now paying to drive on roads they were also paying to maintain. What he did find was universal praise for the greatly improved quality of some turnpiked roads. They must have been truly terrible before. He mentions the road to Baldock, which was famous for being so difficult that travellers often chose to break through the hedge and drive across an adjacent field rather than risk getting stuck. Enterprising farmers created their own gates to bypass the worst sections, posting men at the gates to collect a 'voluntary' toll which, Defoe says, was always paid.

In those days the sheep and cattle eaten by the town-dwellers had to walk to market. The roads were often blocked by slow-moving herds of animals, and their hooves will have done at least as much damage as the gentry's carriage wheels. In winter the roads became so bad that many farmers didn't even try to move their animals to the towns.

The movement of goods didn't stop altogether in the winter months, of course. Packhorse trains could move in any weather. Their importance can be judged by the investment that went into building special bridges for them, like the one shown here. It's too narrow for a horse and cart.

Inland waterways - at that time, mainly the navigable rivers - were used to move material in bulk. Food was cheap in Wakefield (in the early 16th century) because of the town's good water communications. As the volume of goods traffic rose, it began to make economic sense to improve the rivers, despite the objections of the fishermen, and eventually to dig special canals when the rivers did not run where they were needed.

In good weather it was far easier and cheaper to move goods by sea, from one coastal port to another. Adam Smith commented that six or eight men in a 200-ton ship could move the same quantity of goods between London and Edinburgh in three weeks as 'fifty broad-wheeled wagons, attended by a hundred men and drawn by four hundred horses', but at a much lower cost. However, I think he deliberately chose an extreme example. In his day Scotland and even northern England were very difficult to reach by road - the first public stagecoaches didn't run as far as Westmoreland (in the far northwest of England) until late in the 17th century - and a 200-ton ship would have been the largest merchant vessel afloat at the time. (Things actually weren't that much better in the 1830s - Mr. Pickwick's one-eyed acquaintance 'the Bagman', who travelled regularly between London and Edinburgh, returned to London each time 'by the smack'.)

So two questions arise. First, how did turning public roads into turnpikes improve their quality so much, and second, why did it happen then?

Paying for the roads

By 1750 there were turnpikes on a few major roads mostly around London, and it was generally acknowledged that road quality was beginning to improve at last. It was cheaper to transport goods by land than it had been fifty years before. Then suddenly the idea of turnpikes caught on in a big way.

Over the period 1751-1772, a turnpike mania developed, giving rise to 389 Turnpike Trusts, more than in either the preceding four decades or the following 6½ decades. ... By the mid 1830s - on the threshold of the railway age - there were over 20,000 miles of main road controlled by Turnpike Trusts, collecting an annual total of over £500,000 in tolls.

What caused this explosion of interest in the middle of the eighteenth century? Why did so many people all decide at once that turnpikes were a good thing? The answer seems to have been because central government stopped competing for money with the private sector. Interest rates were allowed to fall, despite the loud protestations of some landowners that such a step would lead to the ruin of the kingdom. Christopher Hill describes what happened.

For nearly eighty years before 1624 the official rate of interest (when there was one) remained unchanged at 10%; in the next ninety years it halved. ... After 1714 private capital could not offer more than 5% on loans ... In 1727 the rate of interest on government stock was brought down to 4%, in 1757 to 3%.

So by the middle of the 18th century cheap money was available for entrepreneurs to bid for. If you had £100 lying idle, you could get a better return on your money by investing it in a turnpike than by lending it to the government. It must have seemed a safe investment, too - the road would always be there, and people had to pay to use it, and traffic levels were rising all the time.

The turnpikes were financed by long-term loans. On the face of it, this is rather odd. The usual way of raising money for a speculative venture would be to start a company, write a prospectus and sell shares. No doubt many entrepreneurs would have preferred to do just this, but they were not allowed to. In the government's view, it was giving people the freedom to form companies that had led to the South Sea Bubble fiasco and the financial meltdown which followed. That had been a really scary adventure for the country, and the government was determined that it should never happen again.

It had started innocently enough. The South Sea Company had been formed in 1711 to trade with the Spanish Indies. It was given a monopoly on trade with the region, including the highly lucrative slave trade. (It was to be another hundred years before the slave trade was officially abolished within the British Empire, and existing slaves were not freed until 30 years after that.) The directors bribed many influential figures in government, persuaded the king to become governor of the company, and in 1720 offered to take over most of the national debt - then standing at £50,000,000. The share price rocketed. Everybody expected to see their money double, and then double again, and for a lucky few an investment of £100 did balloon into £1,000 within a few months. In this fevered atmosphere it became ridiculously easy to raise capital for any kind of hare-brained scheme. Then in the autumn some major investors decided to sell. The share price collapsed, and so did the price of all other investments, including government stock. Many people were ruined. Parliament set up an enquiry which threatened to make public the involvement of senior government figures and even royalty in the disaster.

Robert Walpole was one of the few ministers not directly involved in the scandal.

He saved the Court; he saved what politicians he could; he even saved something for the South Sea Directors. He ignored contemptuously the popular hatred he aroused, and used all his parliamentary skill to force through his policy. The ministry survived: the finances of the country were patched up: the dynasty had been rescued from overt scandal.

But a few months later the Bubble Act became law, preventing the formation of joint-stock companies without a specific royal charter. There would be no more Bubbles, ever. (Of course, the Internet boom of the 1990s and the more recent problems with banking were based on the same fantasy of limitless wealth just around the corner. What we learn from history is that we seem to learn nothing from history.)

The Turnpike Trusts therefore had no choice but to raise money from investors by means of long-term loans, which were secured against the expected income from the tolls. Parishes were not allowed to raise loans - their expenditure had to come from income, and many parishes spent nothing at all on their roads. So the result of setting up the trusts was (contrary to what historians apparently used to think) a huge injection of new money into road-building:

... road expenditure per mile increased by a factor of ten after turnpike trusts were established along individual roads.

The trusts did the job properly. They engaged engineers who actually knew how to build roads, brought in labour and materials, hired surveyors, and even bought land when a different route would be better. Until that time there had been an earnest debate amongst armchair theorists as to what profile roads should have. Some argued that they should be concave, so that rainwater washed the mud away, or flat but sloping down to a ditch on one side, or wavy with little hills and valleys to assist drainage. The experts, led by McAdam (who incidentally did not coat his roads with tarmac) said that roads should be convex, with proper foundations, and that is how they were built. The turnpike trusts transformed the muddy quagmires into properly surfaced roads that could withstand an English winter.

The financial operation of the trusts was simple. Their income from the tolls was used first to pay the interest on their debts, and all the money left over went into maintaining and improving their roads. They were not allowed to make a profit. Unfortunately, Parliament in its wisdom had fixed upper limits for the tolls the trusts could charge. They weren't set high enough, and one trust after another was forced to go cap in hand to Parliament and ask for an extension to the time limit on its monopoly. When this was refused, as it frequently was, the trust was wound up without repaying its original investors. Turnpikes were effectively a wealth tax, moving money from private pockets into the infrastructure of the state for the benefit of all future travellers.

A real turnpike near York

In 1768, a few months after the Act of 8 Geo. III c. 22 - which sought to impose duty on the American settlers but had all sorts of unintended consequences (rebellion, war, the Declaration of Independence, cowboys, Hollywood, Microsoft, and so on) - became law, Parliament also approved 8 Geo. III c. 54. This Act brought into being the turnpike trust charged with "amending and widening the road from the City of York to the top of Oswaldkirk Bank" (about 20 miles north of York) and was the culmination of two years' hard work by a small group of local landowners.

One of the Bill's chief promoters was Lord Fairfax, more properly known as 'The Right Honourable Lord Viscount Fairfax in the Kingdom of Ireland'. He didn't live in Ireland. He lived at Gilling Castle, about a mile from Oswaldkirk, and by a remarkable coincidence the new road would run from his castle gates directly to York. Actually, I don't think it was a coincidence at all, because when he was trying to get the Bill through Parliament he wrote to his neighbour Lord Fauconberg to suggest that the road could include a spur that ran directly to the neighbour's house, too. Fauconberg politely declined the offer. But the turnpike would only happen if a majority of the local landowners saw it as being in their own interest. Parliament's approval would not be automatic. Some people opposed the Bill, on the grounds that the tolls would not be sufficient to cover repair costs, or because of the increased costs their tenants would have to bear, or simply because they had not been consulted. Landowners had to make a judgement as to whether the improved road would benefit them (and their tenants) more than the new tolls would cost them. It was far from obvious at the time that good roads were essential, so the decision was not as straightforward as it may seem now. As it turned out, nearly 200 local worthies were persuaded to agree to act as 'trustees' - a role which involved no work and no financial risk - and the Trust came into being.

Two weeks later a few of the trustees met and began to get things moving. They appointed a treasurer, a surveyor, and a clerk, who was instructed to arrange a public meeting in April 'to receive proposals for making the road in particular parts, for building toll houses and to appoint a bar keeper'. The man they chose to collect the tolls was to receive 1s. a day, but had to put up a bond of £20 for his honesty, because the trustees would have no way of knowing how much money he actually collected. In fact, a few years later the trust decided to 'farm out' the toll. This involved selling the right to collect the money - the trust received a fixed sum every quarter from an independent businessman who paid the toll-keeper and took the risk of being defrauded by him. It doesn't seem to have occurred to anybody that fraud would have been eliminated if the toll-keepers had been required to sell tickets that each carried a different serial number. Perhaps the technology was beyond them, or perhaps printing individually-numbered tickets would have been prohibitively expensive.

To finance the work, the trust needed capital. By May half a dozen gentlemen in York had agreed to accept mortgages (at 4%) totalling £550, and by the end of September the trust had £1,000 to spend. The first priority was to build the toll-keeper's house and erect the turnpike itself, not forgetting the railings on either side of the road to ensure that all travellers went through it. Almost as an afterthought, the surveyor was instructed to 'throw up the road over Wigginton Moor'.

And so Lord Fairfax's road to York was gradually improved. By the time the trust was wound up in the middle of the nineteenth century it had debts of close to £5,000 and no way to pay them back (though unlike many others, the trust had regularly paid the interest on its debt). The doubters who had forecast that the toll income would be inadequate had been proved right. In fact, the trust would have been bankrupt long before if it had not been for the continuing contribution from the parishes' Statute Duty - the standing obligation on the parishes to contribute to road maintainance.

Other sources

- A tour through England and Wales, Defoe, 1725

- Life of Thomas Telford, Smiles

- Loides and Elmete, Whitaker, 1816 (quoted in Packmen, Carriers and Packhorse Roads - Hey, 2001)

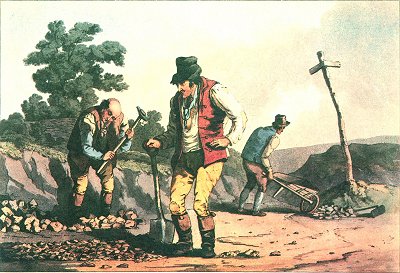

- The Costume of Yorkshire,Walker, 1814

- Life of Thomas Telford, Smiles, ??

- White's Directory of the West Riding, 1837

- Itinerary, Leland, 1545?

- The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

- Pickwick Papers, Dickens, 1830

- The First Industrial Revolution, Deane, 1965

- Reformation to industrial revolution, Hill, 1967

- England in the Eighteenth Century, Plumb, 1950

- Did Turnpike Trusts increase transportation investment in 18th century England?, Bogart, 2003 [Internet]

- The York-Oswaldtwistle Turnpike Trust, Perry, 1977