This essay tracks the 4,700 residents of Swaledale between 1881 and 1891, and explores the reasons why many families moved out of the dale. It names a lot of families and, since migration numbers were not uniform along the dale, it contains a lot of graphs and analyses by district.

By 2008, after a year of researching Swaledale as a whole, people’s names are familiar and I have developed a curiosity about them as families, rather than simple statistics calculated from the censuses. So this essay is much longer, mentions many more names than previous essays, and the research has taken me down intriguing and time-consuming paths. Once one has an interest in a family it is very tempting to speculate, but these ideas are probably best left unpublished. Well, maybe one or two will creep in. And just after starting this essay the news flashed between family history groups about the free trial access to on-line scanned and searchable 19thC newspapers which gave us all such excitement and excuses to abandon friends, family, the ironing, and any current writing.

Post script By 2012, the internet had moved on and these old newspapers are now available directly from the British Library website. Online access to old publications has increased tremendously in the past five years and there are now many routes and many websites. What a boon they are for amateur researchers.

An earlier essay looked at migration from Swaledale over a wider period, and specifically at where the lead miners went between 1891 and 1901. This follow-up looks at the whole population of Swaledale in the decade between 1881 and 1891. I have traced the movements of 4,700 residents of Swaledale and Arkengarthdale, to find out what happened to them.

A copy of the Excel data set on which this essay is based (full Swaledale census transcript plus notes) is already available either from the Swaledale Museum in Reeth or from me by email (see the link on the left). So, no guarantees but you are most welcome to take the data and play with it yourself.

Incomers by 1891

People did still move into Swaledale and Arkengarthdale between 1881 and 1891, as they had in the earlier decade. But now, as well as the expected policemen and schoolteachers and clergymen, farmers and shepherds are also coming in from outside as disillusioned and exhausted tenant farmers move on.

This photograph is of a shepherd’s cowpe (mobile home?) which we saw in the North Yorks museum at Hutton-le-Hole. Is it familiar to dales folk?

There are so few newcomers that it is possible to identify and describe them in detail. I shall start at the top of Swaledale, and move downstream.

In Muker, the new schoolteacher John SOWTER and the new Congregational minister from Scotland - William CROMBIE - have settled in with their families, at least for now, and John THISTLETHWAITE has moved his shoemaking business, and his young family, across from Askrigg to Thwaite.

Four new farm labourers have moved into the district, as have seven new domestic servants. And three young wives, and a grand-daughter. Some locals have returned to the dale: farmer Robert HORSFALL is back after a working lifetime’s absence, gamekeeper Foster KEARTON after a briefer spell in Skipton, game watcher James Brunskill HUTCHINSON, and three more farm labourers. One of the new ag labs was John KILBURN, who moved to Hoggarths Farm from Cotherstone. And Cotherstone is where Robert HORSFALL’s daughter Margaret was born. Was John following teenage lust and moving to be near Margaret? Or did Robert put a word in for him as a good worker. Whatever the reason, John had gone again before 1901 and Margaret was still dressmaking at home, so I guess any lust was one-way.

Farms rarely changed hands

Only one farm completely changed hands by 1891. The AKRIGG family moved out of Black Howe farm on the easterly slopes of Birkdale Common and six HUTCHINSON siblings have moved in from Westmorland. In the 1891 census the eldest son, Lancelot, described himself as a farmer’s son rather than Head of household, which seemed odd.

But the reason for the move may be logistical: in 1881 a William and Margaret HUTCHINSON were farming near Winton in Westmorland with an astonishing fourteen children, aged from 23 down to 5m, one of whom was called Lancelot. Winton is only about 10 miles from Birkdale and I wonder if the parents simply ran out of space and turfed six of the older ones out as soon as they could be trusted to run a farm without supervision? Yes they did, and I found confirmation in the Northern Echo of Monday, May 22, 1882, which reported one of William's sons as being in court for allowing sheep scab on to the farm in Swaledale - presumably the one being run by Lancelot:

So poor William’s trust in his son’s ability cost him £350. The parents are not to be found in any 1891 census, nor are the younger children - did they emigrate? In 1901 most of the siblings are still there, plus a new one in from Westmorland, all still single and all still farming.

The people who moved, reported village by village

Gunnerside and Lodge Green’s incomers are slightly different. A new police officer (they seem to move about quite regularly) but also a new GP and two new grocers move in. And quite a few people move back; including locally-born schoolteacher John J SPENSLEY, milliner Elizabeth SUNTER and nurse Ellen BRUNSKILL. James CALVERT comes back to the blacksmith’s family business, and a couple of widows return to retire.

Low Row gets a new minister when James CLARKE returns to the dale with his Bolton-born family, and the church itself gets a facelift, as reported in December 1885.

"A RENOVATED SWALEDALE CHURCH.- Melbecks Church, Swaledale, has just undergone considerable renovation. A wooden floor has been put down. New open seats of Mernel[?] pine have also been laid, the former seats being old, very cold, and uncomfortable. The church has also been wainscotted on both sides, almost up to the windows. The wood work has been executed by Mr Thos. Petty, joiner, of Reeth. The seats and wainscotting have also been stained and doubly varnished by Messrs Crofts, of Reeth. The following have kindly subscribed towards the cost of the above improvements:- Captain Lyell, lord of the manor of Swaledale, through Mr A T Rogers, solicitor, of Richmond, £10 10s; Misses Simpson and Bonsall, £10 10s; Mr John L Tomlin, of Thiernswood, £5; the Rev. R V Taylor, Melbecks, £5; the late Mrs Knowles and family, £5; Messrs Broderick and Clarkson, £5; Mrs Williams and Miss Garth, £2 10s each; and Dr Turner, £2."

William GILL from Aysgarth has taken over the Temperance Hotel and also runs a grocery and drapery business with his wife Ann. Mary BIRKBECK (another familiar surname but born Penrith) also has a grocery business in the village. There is a new schoolteacher from Lincolnshire, and three farm labourers from outside the dale, but that’s about it.

Healaugh’s decline continues (more about this later). The only economically-active newcomer is Hannah BELL from Westmorland, who takes on a farm in Reeth Lane. There’s a new wife from Richmond, and an aunt and a granddaughter return to help at home.

Lower Arkengarthdale was one of the few districts to see an increase both in households and in birthrate. New families in the upper dale are: Michael WILBY, gamekeeper and farmer from Kirby Ravensworth, Christopher HUTCHINSON, farmer from Hawes, John HIRD, farmer from Manchester, George TEMPLETON, agent and shepherd from Dumfries, James CLEMENT, shepherd from Dumfries. Three new wives, three domestic servants, one farm labourer and one blacksmith apprentice have also moved in. And people returned, of course: Ralph and Mary HARKER, grocers, back from Lancashire with their children; Mary PEACOCK, widowed in Co Durham, back with her two miner sons; Edmund BROWN and his sister Mary left their parents in Barningham and came back to farm at High Faggergill, Thomas HODGSON moves his general dealership back from Marske and the clergyman TINKLER’s daughters have returned from their boarding schools.

Reeth’s incomers were more of the same: the new schoolteaching assistant from Co Durham, the Congregational minister John HARTLEY from Halifax via the USA, with his young family, the slightly older Wesleyan minister Thomas PEARS from Cheshire with his evenly-spaced children each born in a different county. Two pubs in the town had changed hands: the Shoulder of Mutton is now run by Mary SLEIGHTHOLM from Westmorland, and the Black Bull by George and Hannah GARBUTT who have moved over from Bowes in time for three of their children to marry locally within the past few years. And one of the local landowners, George W ROBINSON, is living at Hill House (but where is his wife?).

The chapels are thriving in the town. Much new building has been going on and non-conformist chapels have been popping up all over the dale.

And burning down - Reeth’s Wesleyan chapel had a near miss in 1887:

"A SWALEDALE WESLEYAN CHAPEL ON FIRE.- Early yesterday morning the commodious Wesleyan Chapel at Reeth, in Swaledale, was discovered to be on fire. The people in the neighbourhood extinguished the flames. The pulpit and choir seats were entirely destroyed, and many panes of glass were broken. The damage is estimated at £200."

but here it is (I assume it’s the same one) in 2007:

But apart from a new gardener and farmer, Joseph POSTGATE from Guisborough, there are no more new Heads of household. Daughters, sons and sisters have returned, as has widowed watchmaker George BOTHROYD, who left as a young man. The BRADBURY hold on Reeth’s tailoring trade had been taken over by BLENKIRONs by 1881, but even the BLENKIRON sons have moved on and now they employ a Scot to help out. The remaining incomers are servants and tradesmen: six new domestic servants, a sawyer, a milliner, a bricklayer, a tailor, and a new rural postman from Lancaster. Work is still available for those prepared to fill gaps left by the emigrants, and the workhouse is supplying labourers. And the usual couple of widows have come back to retire.

Fremington had no new incomers but Robert THOMPSON came back from Darlington to run the corn mill (and to lose two-thirds of his meadow land in the summer floods of 1888). Mary PLACE came back from Durham with her dressmaking daughters, and John BOUSFIELD came from Bowes to take over Bank House farm from his sister and her husband.

Grinton’s incomers were also, for the most part, older people returning to retire. The newcomers included the clergyman Percy SMITH, two new wives, two elderly widows and the odd domestic and farm servant.

In Hurst, a new schoolteacher - Joseph H DIXON - arrived at the Board School via Essex, Oxford and Worcestershire with his wife and baby daughter. Charles RETALLICK came up from Cornwall, married the landlord’s daughter and started farming at Hill Top House in Hurst. His sister also came, stayed, and married a local farmer. (There are quite a few Swaledale-Devon links which could be explored, but not just yet and not here.)

But it is Ellerton and Marrick that see the most incomers. Of the eight farming households in the Ellerton Abbey estate, six have moved on. Only the CROADS, land agents, and Thomas FOTHERGILL, shepherd, remain. The newcomers include Edward WOOD from Richmond, his wife Alicia and their ten children (20, 19, 17, 16, 14, 12, 10, 8, 4, 2) and his father-in-law, Fortunately, only one of the eight cottages on the estate had less than 5 habitable rooms, and his was not one of them.

The newcomers are Thomas HODGSON and his family from Stokesley, Henry PINKNEY, joiner and farmer, from Nottingham via Bowes, William SIDDLE came back and married Ann HODGSON, and took on the Manor House, Thomas IRELAND and his family came to Marrick Park, Christopher BROWN and his sister moved up from Richmond

Marrick fared slightly better than Ellerton. Of the 32 households in 1881, 15 changed Heads and 29 are occupied in 1891. And one of those is the obligatory new schoolteacher.

Birth Rate

And the birth rate fell; a sure sign that younger families were moving out

And although the death rate in the dale was fairly standard at between 10% and 12%, the birth rate between 1881 and 1891 was much more varied, and illustrates how many young families left Low Row and Feetham. Allowing for the fact that I have only been able to count those children under 10 who were still alive in 1891, the district birth rate numbers for 1881-91 are:

| District | child<10 | birthrate |

| Muker | 136 | 22% |

| Gunnerside/Lodge Green | 80 | 22% |

| Low Row/Feetham | 28 | 11% |

| Healaugh | 33 | 18% |

| Reeth/Fremington | 95 | 20% |

| Grinton | 58 | 21% |

| Marrick/Ellerton/Hurst | 55 | 19% |

| Arkengarthdale | 191 | 25% |

Moving about within the Dale

One of the early reasons for starting this research was to try and find out how many ordinary families owned their own homes. The most useful data is a rate valuation of the Reeth township for the year 1871, which showed that the majority of homes and many farms were rented. I decided that not much would have changed in twenty years, so there was probably not a great difference in house ownership in the 1880s and 90s. See the separate essay Home Ownership 1870 if you would like more detailed numbers and householder names.

I had my own preconceived ideas - all farmers would stay put, other families would stay put unless dire need or good fortune made them move on, not much would happen. I had not allowed for the birth rate, or the death rate, or more mines closing, or the flexibility offered by renting rather than owning, or the terrible and regular floods of the 1880s.

I do realise that many farms were on long tenancies, often passing to the next generation, so maybe only those upper dale Aldersons actually owned their farms. I decided to assume that if a farming family stayed put from one census to the next, it probably either owned the farm outright or it suited the owner for the family to treat it as their own. If the farming family moved, it probably rented. But I did not see the same need for staying put amongst non-farming families. Miners move if a new seam is opened, or a mine closes, or if their family gets larger. Artisans (blacksmiths, cloggers, dressmakers and so on) could work anywhere but why move unless you have to? Tradespeople were probably attached to a shop or workshop, so would probably not move far. What follows is what actually happened.

This graph shows the percentage of households who moved within the dale between 1881 and 1891. Does a third of the households in your street move at least every ten years? If so, it is not a recent phenomenon.

Every district here has a turnover of more than 35%. There must have been a steady rumble of cartwheels as people moved themselves and their families up and down the dale.

Grinton has the most stable population, with the smallest exodus and largest proportion of "stayed-put". Marrick has the highest proportion of new families moving in but also the smallest proportion of people moving house within the villages - was this to do with tied cottages? Possibly.

The flooding that washed away a whole community

There is a local difference. Low Row is the only district where more people moved house than stayed put, but also it was here that the biggest proportion of the population left for good. Life must have been grim along this part of the valley in the 1880s. This is also where there were hardly any incomers - probably because there was not a lot to come in for. Much of it had been washed away by the flooding Swale in January 1883. The Northern Echo’s special correspondent, understandably emotional, travelled up the whole dale and wrote a long article on Tuesday 6th March, which included:

"Over one of the fields [at Healaugh] is strewn a huge shoal of stones the size of large turnips. The bed of the [Healaugh] beck or gill has been raised several feet by the masses of boulders brought from the hill above. Some of these boulders will weigh half a ton, and yet have been swept along like feathers. The fields on the opposite side of the beck also bear signs of devastation. Returning to the road, we pass on our left Whita Bridge, the approaches of which, with the fences [stone walls] on both sides, have been swept away. The road skirting the right bank of the river for half a mile here resembles the half-dead bed of a stream, for the river has swept over it, and on to the fields beyond, leaving a tidal mark of chips, upon which a select party of crows are sagely meditating, as if at an utter loss to explain ‘this state of things’. The road, gradually ascending, takes us to the contiguous villages of Feetham and Low Row. The hills here form a natural basin, the river sweeping in and through an extensive tract of lowlying land, and passes on to Whita Bridge. For a mile this portion of the valley extends, and throughout its length the deposit indicates that it has been one vast lake."

Changing jobs

Maybe the change of address was caused by a change in occupation. I recorded every resident’s occupation in 1881 and 1891, and made a note if it changed. Children started work, of course, which also gives a clue to the local expectations for what might be a secure job. The following list shows the highlights of what happened to the people who stayed in the dale.

- 36% of men and 30% of women were doing the same work as 10 years before.

- 98 miners decided that they had had enough. 52 of them became full-time farmers; others took up labouring, or shopkeeping, or a craft.. The change affected their wives, too - 38 of them suddenly had to work out how to manage farm work as well as the house and family.

- 85 of the miners’ sons decided that mining was a good job after all, This decade saw a resurgence of leadmining, with new seams being opened up, as reported in the Northern Echo in 1886.

"LEADMINING IN SWALEDALE - DISCOVERY OF A NEW VEIN: For many years the leadmining industry of Swaledale has been declining. It is therefore gratifying to hear that at length there are prospects of a revival of the industry, for the men employed at the Hurst mines, which are backed up by some enterprising gentlemen, have struck a most valuable vein. It is said to be the largest and richest ever discovered since the commencement of the Hurst mines."

But the mine did not last long; by 1891 the company was in liquidation and 68 of that 85 had moved out of Swaledale before 1901.

- 104 young sons and 78 young daughters became old enough to work full-time on their families’ farms.

- 43 girls went into service in the dale, and four became teachers.

- 23 young men took up apprenticeships with tailors or joiners or shoemakers. One of them belonged to John and Catherine FOTHERGILL who ran a draper-cum-grocery business in the centre of Reeth. They sent their young son Joseph Ernest to an establishment of a kind I did not know existed: a hostel at 29 Shakespeare Street, Ardwick, in the centre of Manchester, which accommodated 29 drapers’ clerks and assistants. It had a Scottish matron and two domestic staff. Was it a residential training college? a hostel for the staff of a nearby department store? I have tried hard but have not been able to find out anything more.

- 79 women and 58 men described themselves as newly-retired by 1891, although only ten miners made it to this desirable state.

Age was an influence, too, as you might expect. Young and single people change jobs more readily, and are more willing to go further to find work. Based on the whole population of 1881, I calculated the average age of the men and women who moved away, and of the men and women who stayed. There was a 10-year difference, and it was the twenty-somethings who left, of course, thereby depriving the dale of yet more new families.

Married 1881-91

453 couples married during this decade. In some marriages only one partner was local. I used local parish register transcripts and freebmd to pair up as many couples as possible but I only have access to the Church of England registers, so have no confirmation from non-conformist or Catholic records. The 1891 census produced more spouses, as I tracked down the migrants. When I found a mystery spouse I used the freebmd website to locate the marriage. If there was still a choice of spouses then I used his/her given pob/yob as a means of identification. Some couples who claimed to be married were just not in the record, even though one young man had a mother-in-law and two brothers-in-law in the house in 1891, and I am sure they would not have allowed any hanky-panky.

So I did my best, and took quite a lot of trouble, but did not go as far as requesting marriage certificates. The following statistics and analyses are based on this logical but unproven data.

Of the 1,290 unmarried people who were aged between 12 and 32 in 1881, 40% (522) were married by 1891. And of those, 59% (307) had moved out of Swaledale before 1891, which largely explains the drop in the proportion of locally-born children shown later in this essay. Older people married too, of course, including quite a few in their late 50s and 60s.

I compared the numbers with the marriages in 1851 (see my separate essay) to see what had changed over 40 years. My earlier essay was only concerned with women who had children under 10, and their most frequent age at marriage was 21. I tried to find a matching data set in 1881-91, and decided that any woman marrying under the age of 40 had a good chance of starting a family. This time, I also plotted the ages of the men in these marriages.

The most common age for women to marry has increased from 21 to 23, although by that age almost half of all the women are married. By the age of 25 almost half of the men have married too, and three-quarters of all marriages happened before anyone was 30. It is interesting to see the sudden male increase at the age of 21. Was this only because that was the age at which men could marry without parental permission, or was there some other factor? I do know that apprenticeships usually forbade marriage until 21 so any apprentice who wanted or needed to marry had a problem.

[Irrelevant but interesting: Before 1754, when it became mandatory for marriages to take place in church, this permission problem was solved in the south of England by marriages under what were called Fleet rules, often carried out by parsons in the Fleet debtors' prison in London or in nearby coffee houses. The rules said that a marriage could take place without banns or licence as long as it was recorded somewhere. In one of the registers of such marriages a note had been made that an apprentice had sworn the parson and his clerk to absolute secrecy until he reached the age of 21. Not relevant to Swaledale, but I thought you would be interested, as I was when I discovered a SPENCELEY marrying "under Fleet rules" in 1733 and had to go look it up.]

The graph lines are very similar, with that three-year age difference being continued right across. This does not mean that every 18-year-old married a 21-year-old. About half of all marriages were between couples with an age difference of more than 3 years. When I was marking up the dale and non-dale marriages I thought that the age difference seemed to be much less if the marriage was outside the dale (how intriguing, I thought, why could that be) but no; 49% of marriages outside the dale were by couples less than 3 years apart, 51% in the dale. Another sociological brainwave comes to nothing.

But there is one significant change - as the decade went on more and more of the marriages happened away from the dale. In 1881, 80% of these marriages took place in the dale. By 1891 the number had dropped to 30%. This can only be the result of migration, where children who moved away with their families found their marriage partners in the new towns.

And thirteen other away-marriages have to be fitted in somewhere along the decade - these were the ones where I finally decided I could not trace any marriage record. But the newly-wed couples were all living out of the dale by 1891 and this would make the graph drop even more steeply. Some of these registration districts covered large areas, and the Richmond district creeps just into the dale, so a few of the weddings might not in fact have been all that far away from Swaledale. Bureaucracy can be misleading. I have never been able to understand why my own wedding was in a registration district called Wharfedale (green valleys, villages, sheep) when we actually got married in Farsley, between Bradford and Leeds (big stone terraces, mills, cinemas).

Some couples came back ...

The names of people who returned

Anyway, the following Swaledale couples quickly came back and settled in the district:

- Annie (nee BARNINGHAM) and William Cook ALLINSON, who had both left Longthwaite just after the 1881 census married in Middlesbrough in 81Q4 (why?) but were back bootmaking and dressmaking in Reeth by 1891.

- Mary Ann (nee ALDERSON) and Thompson BLENKIRON married in Aysgarth 82Q1 but came back to Thompson’s farm in Healaugh. Mary Ann’s 18-year-old daughter(?) Jane ALDERSON was still with her mum and recorded as BLENKIRON in 1891, which might cause an irritating search for any descendants.

- Ruth (nee MARCH) and Robert HARPER’s marriage was registered in Ripon in 83Q1; did they come straight back to Hill Side in Arkengarthdale? They were both living with Ruth’s older brother and sister in 1891, and Ruth continued living there after Robert died. There are no children recorded in the censuses.

- John WHITELL went off to Settle to marry his Elizabeth FAWCETT in 1884Q2 and brought her back to Oxnop farm, where they quickly had four children before 1891.

- Thomas BROWN of Low Row married Annie WALLER in Aysgarth and then they settled in Isles. They were a bit slower in starting their family but had two children by 1901, when Thomas was the local highway surveyor as well as stonemason.

- Robert BAINBRIDGE of Marrick Abbey married a Mary Jane GILL in Richmond in 86Q1. Finding her and her family was interesting. Here is the note I made at the time:

Mary Jane GILL living in Richmond 1881 housekeeper for brother Richard BINKS 27 draper. Why Binks? In 1871 Richard is Apprentice Draper in Richmond with what looks like his family two doors away, but no sign of Mary Jane as a sister. In 1861, Moses (44) and Mary Ann (43) GILL of Marske had dau Mary Jane (2), which would fit with the Richmond b reg. Also had Francis BINKS 5, son of Mary Ann and her first husband (says the census). So there is the BINKS link. Mary Jane BAINBRIDGE died Reeth 1895Q2 aged 36. Robert BAINBRIDGE re-married 96Q2 Eliz METCALFE otp.

- Thomas FOTHERGILL of Ellerton Abbey was another mystery. In 1881 his wife was called Isabella, aged 32 b Kirby Ravensworth. In 1891 it was Mary J, aged 44 b Kirby Hill but I ignored that bit. No death registration for Isabella in freebmd 1881-90Q4 but a Thomas FOTHERGILL did marry again. I decided that Isabella must have died and our Thomas had married Mary Jane BROWN in 86Q2 Teesdale. This was my note at the time:

This is the only marriage of a Thos F to a Mary in YNR 81-91. AND she was b Reeth AND she was (U) with farming parents + many adult siblings in Barningham in 1881. AND she is the right age. AND she is not with her family in 1891. But I decided to make a final check before going ahead and writing this paragraph. Everything I said in my note is true but the first clue of impending disaster was that that the Ancestry index for 1891 brought up two Yorkshire Thomas FOTHERGILLs married to Mary. Then I checked the 1891 Ellerton FOTHERGILL census page - was it Mary J or Mary I? The tail didn’t go down below the line. Then I checked for all FOTHERGILL deaths registered in Reeth Q1 1891 to 1930 and there she was, Mary Isabel FOTHERGILL died aged 43 in 1891Q4. Mary J was Mary I. Just goes to show.

So anyone consulting the migration data file already lodged with the Swaledale Museum needs to correct my mistake. And I tell the tale just as a reminder that you can get carried away sometimes.

- Did Hannah CALVERT of 1881 Keld really marry William METCALFE of 1881 Keld in East Ward in 87Q1? In 1891 she fitted all the data for William’s 1891 wife at Kisdon farm. This was my reasoning: Wm's 1891 wife is called Hannah, of the same age as Hannah Calvert, and there is no other trace of Hannah Calvert, and in 1881 he is living next door! But you see what I mean about circumstantial evidence. I would need to see if the East Ward marriage register recorded their fathers, and cross-check from there.

- Henry BLENKIRON of Reeth was easier. The 1891 census says his new wife was born in Coatham. Didn’t know where that was but her mother and sister had moved to live with them so there was her maiden name: DAVISON. The wedding was registered in the Scarborough district so Henry must have travelled quite a distance in his job as a carter - I wonder if he realised what he was letting himself in for as he courted Mary Ann along the Redcar dunes.

- George FAWCETT was a 38-year-old single schoolteacher in 1881 Angram. In 1891 he was living with his wife Mary, aged 41 b Thwaite. Who was she? My Muker parish transcript stops at 1880 so that didn’t help. The only local 1881 person whose dob yob fit, who was not anywhere else, was Mary CLARKE, 31, niece and housekeeper for the CLARKE draper and grocer brothers in Thwaite. But the only marriage record on freebmd is for Burnley, 1888Q3. Did George get a teaching job in between the censuses, in Lancashire, ask Mary to join him, then they married and came back? I don’t know.

- William Graham JOHNSON, ag lab at Crackpot, was born in Richmond and went back down the dale to just outside my self-imposed research boundary, and found Sophia BROWN in Marske. They settled in one of the Ellerton Abbey farms.

- James GILL was one of the young sons who set off to find adventure in the coalmines of Co Durham and came back to Longthwaite with a County Durham wife Jane McKIM.

- Ambrose WHITEHEAD, shoemaker of Arkengarthdale, seems to have married two sisters. His first wife was called Martha Hannah HUTCHINSON, born in Reeth but her parents quickly moved away, and moved about quite a bit, from the places where their various children were subsequently born. Somehow Ambrose kept in touch and they married in Reeth in 1885Q1. Then Martha died in 1890Q1. Ambrose’s second marriage took place a year later in 1891Q1, to a young woman called Edith Isabella R HUTCHINSON b Bowes 1867Q3. Martha Hannah and Edith Isabella R were certainly in the same family household in the 1871 census, in Co Durham, and the pob and yob fit. Show me two Edith Isabella R HUTCHINSONs of the same age and I will change the story.

An interesting diversion into the SWINBANKs - it is surprising what you can glean from the censuses

Finally, all the SWINBANKs at Ivelet Heads got married during this decade, including mum! But why did so many of them marry in Teesdale? Their father, lead miner Christopher, had apparently made a foray into Co Durham after his first wife Bridget died in 1854 and had come back with a second wife (Mary Ann b~1834 Shildon) in time for their first daughter Rosamond to be born in 1858 at Ivelet Heads.

Post Script 2010: Or so I thought. After this essay was published I received an email from Christopher's great-great-grandson, who put me right. Christopher's second wife Mary Ann was in fact the daughter of his first wife Bridget, herself the widow of George WHITE. Mary Ann WHITE (b Shildon) also had an older sister Rosamond (b Gunnerside). Bridget must have come back to Swaledale when George died, and met Christopher. Christopher was b Satron (~1817) and he married Bridget in 1837. George and Bridget had three other daughters - the ones whose marriages I was chasing. Bridget died in 1854, giving birth to little William, who also died. Nobody has ever found anything as formal as a marriage certificate for Christopher and Mary Ann.

From what happened later you will see that nobody then went very far (well, that's not actually true either - see below). Here are the Swinbank marriages, in date order:

- Dau Rosamond (b~1858) to Robert WHITFIELD (b~1850 son of Robt); married 84Q4 Reeth; in Ivelet village in 1891.

- Dau Elizabeth (b~1865) to [another] Robert WHITFIELD (b~1863 son of Thos); married 88Q1 Reeth; in Calvert Houses in 1891.

- Son George (b~1867) to Annie BAINBRIDGE b Mickleton, married 88Q4 Teesdale, back next door to mum in Ivelet Heads in 1891.

Post Script 2012: This Annie was not the daughter of Miles, as I said earlier, she was the daughter of William and Mary (JEWIT) also b Mickleton but a different Annie. In Feb 2012 I received an email from George SWINBANK's gt-granddaughter Susanne, who said in the 1891 census Miles BAINBRIDGE's daughter Annie was unmarried and still living with her father and mother. In fact she was still unmarried when her father died in 1900 and was named in his Will. I am very grateful for this correction, and extremely sorry to have sent Susanne off on the wrong trail.

- Widow Mary Ann to George ALTON (W of Rosemond; at Shaw House Lodge Green in 1881); married 90Q1 Teesdale, back at Ivelet Heads in 1891 with new husband George, his daughter and some grandchildren.

- Son Thomas (b~1863) to Isabel PRATT of Bowes; married 90Q4 Teesdale, still in Bowes in 1891 with his sister Mary as housekeeper.

And to complete the family with Mary Ann’s three step-sisters (corrected again; thanks) and add a bit of spice:

- Step-sister Hannah (b~1848) had m George WHARTON in 1872 and lived at Satron; step-sister Alice (b~1851) had m John LOWES in 1869 and lived in Calvert Houses. Both step-sisters and their families had moved to Oakworth (next to Haworth) by 1891, living as near neighbours in Vale Mill Lane (where, in Nov 2008,

this little cottage was for rent at £485 pcm). The wives would have been able to hear the noise of Mytholmes Mill in their kitchens. The husbands and children were working in the mill. The two older sons were working for the railway company whose line ran past the mill. The only similarity with Swaledale is the nearby presence of a river, but this one carried the effluence from five mills.

this little cottage was for rent at £485 pcm). The wives would have been able to hear the noise of Mytholmes Mill in their kitchens. The husbands and children were working in the mill. The two older sons were working for the railway company whose line ran past the mill. The only similarity with Swaledale is the nearby presence of a river, but this one carried the effluence from five mills.

The only similarity between Oakorth and Swaledale is the nearby presence of a river, but this one carried the effluence from five mills

Footnote Between the two Swinbank sisters lived two more Swaledalers, though they had been away from the dale longer: James ALDERSON (44, b Grinton) was now a "clerk to the Manufacturer (worsted)"; his wife Elizabeth was still there, and there were four children born West Hartlepool. The other household belonged to George BLENKIRON (46, widower, b Grinton), his older sister Margaret, and his seven children. I keep coming across this kind of proximity. It can't be a coincidence and it implies a considerable flow of information between the mill towns and the dales, long before mobile phones and email. These Swaledalers stuck close, and looked out for each other. Quite right too. Other migrants to Haworth are described later in this essay.

- Step-sister Jane (b~1839) never married but had been housekeeper for Thomas WHARTON of Satron long enough to have his children (I suspect) and when he died in 1881Q1 he bought/gave her a house (I suspect) next door to his son John, in Satron, with his other son George and his wife Hannah (Jane’s sister, see above) two doors down. Having been a domestic servant all her adult life, why else would Jane describe herself as ‘property owner’ in the 1881 census? The WHARTON brothers must not have liked this because she and her two children left for Lancashire before 1891. You couldn’t make it up.

And the Teesdale link? One daughter was missing in the 1881 census. I found her - Margaret Ann (b~1861) - working as a domestic servant in Boldron, Teesdale, for farmer William White and his wife Hannah. Their son John WHITE was also on the farm and in 1884Q3 he married Margaret Ann, and they stayed on at Boldron, Bowes 2 miles away, Mickleton 10 miles. My goodness, it has taken me all morning to sort this out. Maybe young George met Annie whilst visiting his sister. Maybe Thomas met Isabel at George’s wedding. Maybe Mary Ann and George Alton decided to have their wedding in Teesdale because half her family was there already. There might have been a really good local pub which did good weddings. Quite fancy half a pint myself now after all this.

With data only being available every ten years, it is almost impossible now to say how many of these marriages happened because whole families moved and their children just grew up elsewhere, and how many marriages were between young people who had decided for themselves that they had to move away to make a better life, or had found a wife outside the dale. Although, actually, if a marriage partner was recorded as a son or daughter in the 1881 census then ... Yes. I can go further. Of the marriages which took place before 1891 outside the Reeth registration district, only four were of men in their 20s and 30s who had moved on first. I think this means that most of the families who moved out had very young children, not old enough to be marrying before 1891. The four sons I did find are:

- Joseph PEACOCK, farming with his older brother at the top of Arkengarthdale in 1881, who moved just over the hill into Teesdale to farm at Scargill near Barningham with his new wife Elizabeth Eleanor CALVERT and three ag labs;

- John Thomas FAWCETT, an apprentice blacksmith in 1881 Arkengarthdale, who might have married Hannah SLACK from the CB Yard (no freebmd or PR hit, very few clues, she is the best match and nowhere else in 1891) and moved to County Durham;

- George BRODERICK of Summer Lodge, Grinton, who was a land agent in 1891 Hawes town with a wife called Jane Ann (HODGSON? - the only dob/pob match in the 1891 census index, but no freebmd hit for a marriage anywhere in the country);

- James TAYLOR, a pupil teacher b Melbecks and lodging in Feetham who married in Huddersfield and was a sewing machine agent in Darlington in 1891. The only freebmd marriage match was Ellen BLACKBURN, a milliner and dressmaker of Almondbury (near Huddersfield). I speculate that he decided there was not enough money in teaching, read an article about the heady life of the sewing machine agent, moved to the West Riding, met Ellen and sold her a sewing machine, and whisked her and it off to glittering Darlington. I might be wrong.

John Thomas REYNOLDSON might be one of the very few who moved away first then married an also-moved-away Swaledale wife. Elizabeth Ann COATES had moved to Nelson, Lancashire, with her parents, from Kisdon in Muker district. John was a drainer, lodging much further down the valley at Harkerside. Did they know each other before they met in Lancashire? However they met, they married in Burnley district in 86Q4.

All the rest of the non-dale weddings were because the whole family had moved out and the children/teenagers grew up elsewhere. So there is the answer.

Died 1881-91

I give the significant death rates for the various districts elsewhere in this essay. Now I want to illustrate the death rates of young children, young mothers, and of men in their prime. Again, I had to take their ages at 1881 and then see where they were in 1891. Here are the numbers, using the 1881 ages of each group. The table shows the total number in each group, the number who died, and the death rate as a percentage.

Deaths in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale 81-91 of children aged 0-12, women aged 20-40, men aged 41-59:

| District | child 0-12 | died | % | women 20-40 | died | % | men 41-59 | died | % |

| Muker | 245 | 11 | 4% | 120 | 15 | 13% | 74 | 19 | 26% |

| Gunnerside (Melbecks) | 175 | 7 | 4% | 81 | 7 | 9% | 45 | 8 | 18% |

| Low Row (Melbecks) | 205 | 12 | 6% | 97 | 8 | 8% | 46 | 12 | 26% |

| Healaugh | 92 | 7 | 8% | 35 | 2 | 6% | 20 | 5 | 25% |

| Reeth+Fremington | 166 | 12 | 7% | 116 | 7 | 6% | 61 | 12 | 20% |

| Grinton | 98 | 2 | 2% | 61 | 3 | 5% | 30 | 5 | 17% |

| Marrick/Ellerton/Hurst | 119 | 7 | 6% | 42 | 4 | 10% | 34 | 6 | 18% |

| Swaledale total | 1100 | 58 | 5% | 552 | 46 | 8% | 310 | 67 | 22% |

| Arkengarthdale | 324 | 19 | 6% | 146 | 9 | 6% | 83 | 25 | 30% |

| TOTALS | 1424 | 77 | 5% | 698 | 55 | 8% | 393 | 92 | 23% |

The latest equivalent figures available for England as a whole (2006, from statistics.gov.uk) are:

| Children 0-12 | less than 0.5% |

| Women 20-40 | less than 1% |

| Men 41-59 | less than 5% |

Many men and women were widowed young. Families helped - mothers or sisters came to housekeep; widowed daughters took their children back to their parents’ house. Many re-married. Somehow they survived. But it must have been heart-breaking.

Stay or go?

Here is a summary, by census district, of what had happened to every 1881 Head of household in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale by the time of the 1891 census

The Head of Household’s occupation also had an effect on whether the family moved house, moved away, or stayed put. Here is a summary of what had happened to every 1881 Head of household in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale by the time of the 1891 census. I have grouped the occupations into types, to keep the statistics simple. So ‘artisans’ means blacksmiths, stonemasons, dressmakers, joiners, cloggers, and so on; ‘commerce and trade’ means innkeepers, butchers, grocers, agents, mine owners and so on, and ‘professionals’ means clergymen, doctors, policemen, teachers, and so on.

| Occupation type | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 20% | 21% | 39% | 20% |

| commerce/trade | 19% | 13% | 57% | 11% |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 19% | 11% | 50% | 20% |

| miners/labourers | 20% | 20% | 22% | 38% |

| retired+widows | 65% | 10% | 16% | 10% |

| professionals | 21% | 4% | 32% | 43% |

The differences show up even more clearly when the numbers are put into a graph:

The following paragraphs show the same information, separated out into the various districts (actual numbers this time, not percentages). Please note than when checking migration from 1881 to 1891, the vagaries of the enumerator sometimes made it difficult to decide whether people who stayed in the same village might have changed houses for one reason or another. But if I could fix them relative to others who also stayed I have assumed that they were still in the same house.

Please also note that this time I have allowed for families to take over, so the died column shows the number of people who had died without the family taking over the farm or the business; and the stayed put column allows for someone younger in the family taking over.

Muker census district (Birkdale to Satron) by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (205 of them)

In the farmlands of the Muker district, 13 farms were passed down to the next generation, 38 farming families stayed put and 8 farming families moved to other farms in the district. In the non-farming households, movement was a bit more common. In 1881 the average age of the Muker Heads of Household was 52. The death rate for the whole Muker district was 17%, which was the highest in the whole dale, and a consequence of the older-than-average population.

| Muker by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 12 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| commerce/trade | 21 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 1 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 95 | 14 | 8 | 52 | 21 |

| miners/labourers | 39 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 17 |

| retired+widows | 39 | 27 | 3 | 7 | 2 |

| professionals | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Melbecks1 (Gunnerside and Lodge Green) by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (131 of them)

This district had a different mix of occupations, with the concentration of mining families in the villages, and farmers on the outskirts. In 1881, the average age of these Heads of Household was 48. The death rate for the whole of this district was one of the lowest, at 13%, but highest amongst the women aged 41-59, of whom 23% died. Half the miners and labourers left the dale, as did the district’s only GP and the only teacher. Proportionally more farmers moved house than in Muker, which could mean that more farms in this district were rented than in Muker.

| Gunnerside by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 15 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| commerce/trade | 11 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 22 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| miners/labourers | 66 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 26 |

| retired+widows | 14 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| professionals | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Melbecks2 (Smarber/Low Row/Feetham/Kearton) by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (139 of them)

These communities were much more spread out, stretched as they are along the river bank. In 1881 there was a higher proportion of lead workers here, including smelters, and the mine owners themselves. The average age of all Heads of Household was 47. The death rate for the population as a whole was 15%, but highest amongst men aged 41-59, of whom 26% died.

| Low Row by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 12 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| commerce/trade | 12 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 21 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| miners/labourers | 72 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 39 |

| retired+widows | 20 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| professionals | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Healaugh by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (61 of them)

This is the smallest census district, being concentrated mostly in the village itself but scooping up some of the households on the lower slopes of Arkengarthdale. Here the average age of the Heads of Household was 51. The death rate for the whole population was 14% but it was the highest in the whole dale for both men and women in the age group 41-59, of whom 27% died. The high proportion of farmers who stayed put suggests that they either owned their farms or were long-term tenants. But of the 24 farmers shown as occupiers in the 1870 rateable valuation data, only 3 owned their own houses. It can’t have changed much in 20 years so these 1891 farmers who stayed put are more likely to have been long-term tenants.

| Healaugh by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| commerce/trade | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 30 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 6 |

| miners/labourers | 15 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| retired+widows | 8 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| professionals | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arkengarthdale by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (225 of them)

It seemed too sweeping to count the residents of Arkengarthdale in one lump. But Healaugh has already taken care of the people who live at the bottom of the dale, and the remaining number of households is only slightly bigger than Muker district, so I shall keep them together for this analysis. The largest proportion by far are miners, which include a few coal miners at the top of the dale. Most of the farmers who stayed, stayed put, which suggests that they were owners or long-term tenants. The average age of Heads of Household was 47. The death rate was 14%, with the most affected age group being men aged 41-59, of whom 30% died. This is the highest male death rate in the whole of Swaledale and Arkengarthdale, and reflects the proportion of the male population still working in the mining industry. The number of widows who are heads of household, either as housekeepers for their miner sons or as charwomen just getting by, is also a reflection of the high death rate amongst these working miners and is the highest number in the whole of Swaledale.

| Arkengarthdale by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 11 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| commerce/trade | 17 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 52 | 11 | 4 | 26 | 11 |

| miners/labourers | 111 | 29 | 23 | 38 | 35 |

| retired+widows | 17 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| professionals | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

Reeth and Fremington by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (150 of them)

Reeth was the dale’s centre for commerce, trade and artisans. This was where most people came for their best shoes, or a special hat, or to hire a tradesman, to be measured for a suit, or place a large grocery order. Reeth had four pubs (although two had closed by 1891) and frequent market days and fairs, so it was a good place to retire to, too, if you could choose where to live. Most of the carriers were based in Reeth and between them made regular runs into Richmond, so you came here first when you need to go to the bank or the dentist. The post was delivered here daily from Richmond, for onward transfer up and down the dale. It was a busy place. So there was a much lower proportion of ordinary workers and labourers here. Fewer people left completely. The average age of Heads of Household 51. The local death rate was the dale average of 14%, with no particular age group standing out as being hazardous. The high availability of housing meant that people moved house more, too, and had a better choice when renting. By 1891 there were 39 empty houses in Reeth, and 11 in Fremington.

| Reeth+Fremington by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 34 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 8 |

| commerce/trade | 27 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 6 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 23 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 13 |

| miners/labourers | 33 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 13 |

| retired+widows | 24 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| professionals | 9 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

Grinton by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (88 of them)

This census district included all of the farms and houses along the south bank of the Swale upstream as far as Crackpot, as well as Grinton village itself. Although the smallest census district in population, Grinton parish originally enclosed the whole of Swaledale. It had the only parish church, the big houses and, in earlier times, most of the dale’s weddings, baptisms and funerals. However, during the decade 1881-91, of the 380 weddings in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale only 95 now happened in Grinton parish church. The ageing of the population which has been shown in other districts was happening here too, with the average age of the Heads of Household being 51. The death rate was 13%, with the surprisingly highest rate in the dale for 13-19-year-olds.

| Grinton by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 6 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| commerce/trade | 8 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 45 | 5 | 8 | 27 | 5 |

| miners/labourers | 17 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| retired+widows | 8 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| professionals | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Marrick/Hurst/Ellerton by occupation of 1881 Head of Household (74 of them)

Marrick and Ellerton had the highest turnover of population but the lowest drop. This has to be because of its predominantly farming population, and the fact that even though a tenant farmer might want to move on, the estate has to keep farming. Hurst and Washfold had dropped from 55 households in 1851 to 33 in 1881 and 28 in 1891. Because the numbers are small I have kept the statistical split to a combined total, as I have in all the other analyses. The average age of the Head of Household was 50, and the district death rate was 14%, with no unusual peak.

| Marrick/Hurst/Ellerton by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| commerce/trade | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 37 | 8 | 2 | 17 | 10 |

| miners/labourers | 16 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| retired+widows | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| professionals | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Totalling the whole dale by Head of Household:

| Swaledale & Arkengarthdale by 1891 | total | died | moved | stayed | left |

| artisans | 100 | 20 | 21 | 39 | 20 |

| commerce/trade | 101 | 19 | 13 | 58 | 11 |

| farmers/gamekeepers | 325 | 61 | 37 | 161 | 66 |

| miners/labourers | 383 | 75 | 76 | 85 | 147 |

| retired+widows | 136 | 88 | 1 | 22 | 13 |

| professionals | 28 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

Population drops

By 1891, the population had dropped from 4,700 to 3,200. Some groups were affected more than others. This graph shows how different groups in the population changed between 1881 and 1891. The most significant drop was in the proportion of children - down from 34% of the population in 1881 to 20% in 1891, emphasising how many young couples and families had moved away. Then the miners, from 14% to 6%. Only the elderly population increased as a proportion of the total.

In 1881 there were 1,071 busy households in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale. By 1891 a quarter of those households and almost half the population had gone.

Leavers by 1891

Whilst searching quite separately on my mother’s side of the family I had one of those serendipitous moments when I found a James RAW b 1808 Healaugh, living next door to a pub in Bowling Bradford, in 1881. His adult children were all born in Clayton, Bradford, so he had long left the dale. As I found out when researching Haworth (see below), he was one of the very first to leave.

For ever

Some Swaledalers left permanently. The 1881-91 death rate was quite evenly spread - between 10% and 12% in each district. Low Row had the lowest at 9% (probably because many more of them just moved out); Muker and Marrick, the big farm districts with the highest "stayed-put" numbers, had 13%. Just under 600 of the 1881 population had died in the dale by 1891.

Just vanished

Others just vanished, and it is a weakness in my statistics that I have not been able to track every single person. 189 of the ones who left were not born in the dale anyway: the families of the five church ministers, two policemen, four teachers, two innkeepers and one tinsmith accounted for 102 of them. The remaining 87 were mostly visitors, lodgers or servants who happened to be in Swaledale in 1881 but had no real roots there. Poor Henry SPARK must have been alarmed by an officious census taker who met him on the road and insisted on writing him down - the census describes him as "vagrant accosted in passing through Longthwaite", age not known, place of birth not known. I bet he didn't stay long.

Emigration overseas was probably slowing down by now. The great rush of the 1840s and 1850s took many families away for ever. The newspapers were still advertising but now they offer hot and cold baths and high-class cuisine - very different from the appalling conditions of thirty years ago:

But what were still thought of as "the colonies" were still trying to tempt farmers away - probably not a difficult choice for many of them. If he had £5 5s (five guineas) a farmer could get an assisted passage to Halifax or Quebec, and many did.

A further 121 who had been born in Swaledale have really vanished. It was initially nearer to 250 but by checking the censuses in 1891 and 1901, and marriages and deaths, and looking for them all just by their first names, dob and pob, in case the women had married or the men were mis-transcribed, and with help from one of the dalesfhs email group (thanks again, Ian) I got it down to 121 untraceables. Only a few were whole families:

- Alice HUGILL and her daughters (and she might have married Richard BARNES but then they vanished)

- John and Alice NICHOLSON of Feetham, and their daughter Sarah b Shildon 1879 [subsequently found for me by a dalesfhs member: arrived in Susa 1880; the 1900 Federal census for Springfield/Sangamon/Illinois shows John b 1875, Sarah b 1879, Allice b 1884. Then John 66 and Allice 77 were in the 1920 Federal census but not 1930; no death dates for either.]

- Elizabeth ALDERSON, widow of Isaac, of Plantation, and her sons Jonathan and Luke Raine (not the one in Bradford)

- William and Rosamond THOMPSON of Ten Trees

- Robert LONGSTAFF of Pepper Hall, his sister Ann and daughter Jane

- George and Elizabeth SLACK of CB Yard, and their sons William and George Robert

The rest were sons and daughters, servants and lodgers. The complete list is on the file lodged at the Swaledale Museum, and if you cannot get there and would like a copy for yourself please email me. I need help from family history researchers who know much more about the individual families than I will ever do. I have gone as far as I can using easily available data. I have been told about one family which definitely emigrated, and found a one or two more who might. But emigration records for that part of the century are harder to search when you are looking for many different people, and I did not try.

Thomas and Hannah BELL and their children Mary J, Alice, Elizabeth and John emigrated from Blades to Iowa, and all eventually died there. George SUNTER married a Westmorland girl in 1884, left Lodge Green for New Zealand, was widowed there, and came back with his son Christopher in time to be counted in the 1901 Appleby census. George’s brother Christopher also vanished; I wonder if he went to New Zealand with George, and stayed there?

Could be traced

However, the remaining 4,429 were findable and the rest of this essay is concerned with where they went, and maybe why.

By 1891, 19% of the population had moved house within the dale, 27% had stayed put, and 11% had died. And the stark fact is that the remaining 42% of the people living in Swaledale in 1881 had moved out by 1891.

Incomers and new babies only added back enough to make this an overall drop of 32%. Loss was greatest in the Low Row / Feetham stretch of the dale, where the population dropped by 60%. And I later found out why. The smallest loss was in the Marrick/Hurst area, with the highest turnover of people but a population drop of only 17% overall. Migrations are given in detail in the next section.

Migration destination varied, depending on where in the dale the family lived. Muker emigrants mostly went to Lancashire. Gunnerside migration was spread out more, with 15% going to Lancashire, 9% to the West Riding, and 7% to County Durham. Low Row/Feetham migrants went mostly to County Durham (21% of them) or to the West Riding (13%) or Lancashire (7%). Arkengarthdalers went to County Durham. Most of the Reeth and Fremington migrants went to the West Riding (12%) or County Durham (9%). The few who left Grinton went to County Durham or the West Riding. Most of the people who left the Marrick district went farming elsewhere in the North Riding or to the mills of the West Riding.

As had happened ten years earlier, the age, skills and physical strength of the family members had a lot to do with where they moved. If a family had a number of young children the spinning mills were waiting to employ them and their mothers. The fathers changed from working long and dangerous hours underground to long and boring hours in the mill warehouses, and were probably thankful to do so.

Cowkeepers

Cowkeeping in cities became a real possibility

Some dairy farmers managed to find new markets by providing fresh milk in the rapidly growing industrial towns of Lancashire and the North of England. In fact, I am only here to write this piece because my Bradford-based great-grandfather caught a train up past Skipton one day in search of supplies for his milk dealership. The milk-dealer's young widowed daughter (her photograph is in another essay) soon met the dairy farmer's son, and my dad was the eventual result. But that milk deal happened in the 1890s. The town demand for fresh milk had started much earlier. The absence of refrigerated lorries 150 years ago meant the best way to supply fresh milk was to take the cow to the town.

And so they did, in their hundreds.

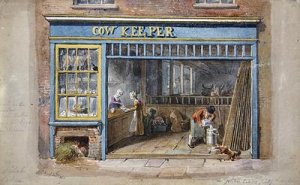

I found this unattributed painting on the internet; the only clue was "1825". The reality was probably a bit muddier although I read later of the annual Gold Medal awarded by the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Society, between 1883 and 1899, for the Best Kept Shippon and Dairy. Good hygiene meant good business.

Enterprising Swaledale dairy farmers took advantage of the railways and sent cows off by rail. The link to Liverpool was good, and West Derby (an ancient manor and confusingly now a Liverpool suburb) was one of the local supply points.

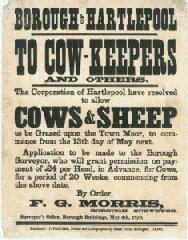

Other dalesmen went east to the coal towns, where local authorities were not slow to find an opportunity of making money too - renting pasture at £4 per cow sounds a lot to me (the poster is dated May 1870) but it must have been worth it. Some farmers sent their younger sons off to operate the distribution end of the business and return the cows to pasture when their yield dropped; sometimes the whole family moved.

Here are the local families who switched to cowkeeping during the period 1881-91:

- George (lead miner b 1849) and Ann ALDERSON took their children Margaret, James and Mary to West Derby. In 1891 George was cowkeeper and milk dealer, and James an apprentice blacksmith.

- Joseph (stonemason+farmer b 1825) and Agnes CROFT left Watson House, Healaugh and set up cowkeeping in West Derby. Joseph died in 1886 but Agnes carried on the business. By 1991 her son Joseph was her dairyman and her son Michael had become a police constable, married with three daughters all b Liverpool.

- Mary DUNN b 1850, dairymaid and unmarried dau of widow Rosomond in Ivelet in 1881, vanished from the dale but I found a death in West Derby 1884Q1 for a woman of the same age, so I wonder if she went off to relatives to help out, then died?

- Ralph HARKER (lead miner b 1861) left Pear House, Lodge Green, and went to be a cowkeeper in Everton, Liverpool, with his brother Thomas (who must have already been there).

- Robert (farmer b 1837) and Mary Jane HIRD left their 100-acre+ farm at Ellerton Abbey and set up as cowkeepers in Bootle, Lancs. Could find no further trace of their son John William b 1874.

- Siblings Thomas (lead miner b 1859), Dinah (b 1861) and Ralph (scholar b 1871) LOWIS left Ivelet Heads and went to Garston, Lancs. All three are described as cowkeepers in 1891.

- James MARCH (lead miner+farmer, unmarried, b 1837) left Show Bottom at Hurst after 1881. Couldn't find him in 1891 but in 1901 he was a cowkeeper, still unmarried, in Loftus, Cleveland.

- Margaret PEACOCK, already a widow in 1881, left her farm in Healaugh and set up as cowkeeper in West Derby with her son John (b 1866). In 1890 her daughter Sarah married George PEACOCK from Daggerstones and he joined the family business in West Derby.

- Robert SPENSLEY (shepherd b 1854) took his wife Margaret Ann [nee ALDERSON] and baby Elizabeth to Kirkdale, Lancs, where he was a cowkeeper in 1891.

- Thomas URWIN (carrier b 1855) left the family carting business in Low Row and went to Long Benton, Tynemouth, where he married a local girl and by 1891 was set up as a cowkeeper with wife, brother-in-law, and two young men Thomas (19) and James (17) BIRKBECK - both b Liverpool but a very familiar Dales name (although I can't trace them back). He also had two servants - must have been a busy little enterprise.

- James and Mary WETHERALD, both b 1852, left their 50-acre+ Heugh Farm, Satron, with their sons Albert and George and went to West Derby. In the 1891 census James and Albert are described as cowkeepers.

A Dalesfhg member sent me "Cow-keepers from the Pennine Dales", an article written by P J Mellor and published in the Dalesman in May 1978. From this article I have extracted the following interesting facts:

- Cowkeepers came from anywhere west of the Pennines. Cumberland and Westmorland names occur frequently in the West Derby and Liverpool censuses as do names from Wharfedale, Wensleydale and Swaledale. Particularly after 1870, whole extended families decided that the lucrative milk trade was a better bet than ever-increasing farm rents.

- Cattle for the milkhouses were bought, newly calved, often fourth, fifth or sixth calvers and kept throughout lactation. This varied but was usually about 18 months. Cows were usually replaced when their yield dropped below three gallons a day. They were then either sold for beef or sent to the country to re-calf. By the end of the 19thC 4,000 head of cattle were being kept within the Liverpool boundary and replacement stock was being bought from cattle marts as far away as Oswestry and Kendal. Cattle were driven through Liverpool by the dealers and dropped off, a few at a time, at the various milkhouses, to the consternation of the local population: "There's a bull loose" was a common cry.

- For the most part the cattle were kept indoors and fed rich rations (during milking, to keep them still): a mixture of brewery waste, molasses, Indian linseed and pea meal, all pre-soaked in warm water. [I suddenly remembered a visit we made a few years ago to one of the many windmills in the northern part of France, where the mill was originally designed and built to crush flax, extract linseed oil, and bash the residue into cattle cake. Now I can understand why, and how the cake was used. I'm sorry if this is all old news to some of you; it was new news to me.]

- Grass from local parks, cemeteries and verges was collected and fed to the cows during summer. Milk and butter were yellow in summer when the cattle were eating grass, and white in winter when they were consuming hay.

I find the "end of almost every street" part of the following quotation hard to credit, and plan to check the West Derby census returns in detail. I see another essay topic crystalizing!

"The Cowhouses, all of a similar style, were purposely built on the end of almost every street. Constructed of brick, they comprised a large house with dairy, shippon, hay loft over stables, trap shed, muck midden and a cobbled yard all within high walls and wooden gates. Milking began at 5am followed by the milk round at 7.30am. Afternoon milking took place at 3pm and the milk round at 4.30pm, finishing about 6pm.

And, returning to the subject of quality of milk and quality of life, the following quotation completes this section:

"Most of the premises were officially called dairies but the proprietors always referred to themselves as cowkeepers and their premises as milkhouses, for there were other dairies which sold only "railway milk". This was brought in by railway from the countryside and soon went sour. The cowkeepers' milk was always fresh and they took great pride in the superiority of their product .. [but] .. the work was arduous and the hours long. It was a seven day week, all-the-year-round occupation. The only time off was an hour on Sunday for church-going."

No change there, then.

Floods

The awful floods

I came upon the newspaper reports of the 1880s flooding as I was coming to the end of this essay and suddenly, instead of a calm and sometimes lighthearted analysis, I was faced with stories of real hardship and despair and the awful ripping apart of these dalespeople’s lives.

The England of 1881-1891 experienced an awful series of floods, nothing like it for a generation, and the newspapers of the time published one heartbreaking report after another as the decade went by. Here are extracts concerning Swaledale, condensed from the Northern Echo, the Leeds Mercury, and occasional newspapers from further away. A full set of my electronic newspaper "weather" cuttings (1861-1900) is held at the Swaledale museum in Reeth but it may well be incorporated into a larger collection to be held there.

1882

December: "In Swaledale, above Richmond, snow has accumulated to a great depth. Several houses are partially buried, and hundreds of sheep have been lost on the moors and hills. Two horses have been found dead in the snowdrifts. Yesterday (12th) the thermometer registered 15 degrees below freezing. Snowdrifts of 6’ start near the Bellisle and continue [upriver] for many miles."

1883

January: "The Gunnerside, Islet and Thwaite bridges, and Eskeleth Bridge, have been swept away. Swaledale is described as a perfect wreck from end to end. The inhabitants of cottages in the lower part of Reeth were awoken at 3am by the noise of water rushing into their houses. A 100-yard slide of rock and earth has blocked the Richmond road near Downholme Bridge."

February: "Scores of acres of land next to the Swale have been turned into a perfect wilderness, being thickly covered with sand." [contamination from the lead mines would kill sheep and cows and take years to leach away or cost £thousands to clean away]

March: "Acres of land have been irreparably injured. Persons have been reduced to absolute distress, with impoverished tenants being reduced to absolute beggary." [see also the fuller quote above concerning Healaugh, Low Row and Feetham.]

1884

January: "There was a heavy fall of rain yesterday in North Yorkshire. The turnpikes were impassable. Considerable damage has been done."

1886

January: "On the moors in the Swaledale district many sheep were buried in the snowdrifts, which were a great depth. Large numbers were extricated with difficulty."

March: "The most severe storm of even the present severe winter visited this neighbourhood yesterday. It has been almost impossible for shepherds to stand out in the blinding storm, and the agricultural outlook is becoming one of unparalleled gloom and depression. It is now certain that they will be obliged to buy hay; hay buying is regarded by farmers as the high road to bankruptcy. [Households] are without coal and have to keep their fires on by burning their furniture. Numbers of sheep are dying of starvation. All the mountain passes are blocked. The drifts in some of the fells are from 30 to 40 feet deep. Hundreds of tons of hay are being daily carted up the dale."

May: "Hundreds of lambs have been lost. Mr Iveson of Moorcock has lost about 100; as has Mr Guy at Schoolmaster Pasture. The ewes and lambs were overblown by the snow but most of the ewes managed to struggle out, and left the lambs to perish on the moor."

1887

January: "In consquence of the rapid thaw the river Swale is rising in the most alarming manner."

July: "The prolonged drought has almost dried up the Swale, Wensley and Ure, the beds of which are visible in many places. The highways are thick with limestone dust and the crops are parched and stunted. Cattle feeding is becoming a difficulty."

1888

February: "Roads are blocked in all directions and yesterday large numbers of men were employed cutting the huge drifts. Arkengarthdale people who attended Richmond market are snowbound and detained at Reeth. Many farmers are snowed up and to fodder their stock is at present an impossibility. Dense fogs envelop the hills above Richmond."

May: "Sleet fell in Swaledale yesterday morning."

July: "One of the most disastrous floods ever experienced in the district swept down Swaledale and Arkengarthdale last night. Several bridges were washed away, houses were flooded, garden walls and produce carried away, and some thousands of pounds damage done. All meadows and low-lying grounds are under water and some sheep and cattle have been drowned. Messrs Thompson of fremington Mill have lost two-thirds of their meadow land. Mr William Cottingham, of Gunnerside, who sustained a loss of £500 in the great flood has now lost £300, for not only the grass but the soil has been washed away. Mr Kendall of Swale Hall, Grinton, has had 20 acres of meadow land rendered useless. Many others are serious losers and the small farmers can ill afford to bear the loss. Many thousands of trout and other fish have been picked up on the land."

August: "On 25th August, 3.18" of rain fell on Upper Swaledale in the one day."

[long report to Richmond District Highways Board included...] "At Rowleth Bottoms (Melbecks) the river has caused considerable damage, having overflown its banks and washed away the wall adjoining the river, filling up the bed of the river with stones and gravel.... At Gunnerside the large bridge is entirely swept away, also the road leading from the village to the bridge for about 500 yards, rendering it impassable by the beck which flows through the village [which now] rushes over on to the road, breaking up the roadway from four to six feet deep the whole length. An Arkengarthdale the Beck has done much damage throughout the dale. The foundation of the Whaw Bridge has been dangerously undermined ... by boulder stones and trees brought down the dale by the force of the flood. The Muker Beck road has also given way."

1889

March: "Gunnerside bridge is still not re-built. Local landowners are asking too much per acre for their land."

1890

January: "Swaledale was on Saturday visited by an unusually furious gale and a flood which surpasses anything since the memorable flood of 29th January 1883. Mr Edmund Knowles of Gorton Lodge, Low Row, has his land all under water, and he must be one of the greatest sufferes in the district [and his tenants, don’t forget]. Horses, sheep and pigs have been seen floating down the river in the course of the day. Gunnerside new bridge, recently built at a cost of £1,000, has been completely washed away, and damage has been done to Low Whita bridge approaches."

Prices, and free trade

The threat to farming

As well as the awful weather, political and economic decisions were also having an effect, especially on tenant farmers. Here is a quote from a Swaledale farmer, interviewed at length in a newspaper report of 1892:

"We must have our rents lowered. If I had not a son, a strong lad 20 year old, and we worked inside ourselves, we could not pay our way. I cannot afford to pay any hands, and it is hard to have to work and get nothing for it. Any farmer who commenced two or three years ago with a small capital must be getting very near the end of his tether now. Many people have grazed stock all the season, and will be worse off for it, because they will not get any more, and probably something less, for them than they paid in spring. I bought some stirks last spring, and shall try and keep them through the winter, but if I had employment to pay for I could not have done it. The butter trade is bad and prices are low. That, again, is because there is so much foreign stuff in the market. There is free trade into England and everything that goes out of it has to pay. We let too many foreigners in; and I think we ought to put a duty on dead meat.... Three years ago stock was selling pretty well, and everybody went in for rearing young calves. Now that they are doing so badly they may drop off again, and prices get up. I hope it will not be too long first, or we’ll all be beggared."

The report went on to say:

"It is asserted that in every particular this year has been worse than any of its pre-decessors for the last quarter of a century, as although 1887 was a disastrous year for horned cattle, sheep were nothing like so unremunerative as is now the case.... The unpropitious season is agreed to have been the chief inducing cause of the depression, but this has been aggravated by what are considered the excessive rents, as well as by the largely-increasing importations of dead meat from America."

It is not surprising that many Swaledale families decided that the solid pavements of the West Riding and Lancashire, and being paid by an employer to work indoors, would be preferable to such misery and hardship.

Migrants to Haworth

And so to Haworth

Because my oldest friend lives in Haworth, I have investigated the 19thC town in some detail, including making transcripts of the 1871, 1881 and 1891 censuses. Haworth is up on the moors above Keighley and is the West Riding mill town closest to the Yorkshire dales. Bleak and windswept, even now you can walk out of the town on to the moors, which would have given an illusion of familiarity to the migrants. The 1880s and 90s Heads of Households, often their wives, certainly their children, all worked at the many jobs which made up the textile trade, from washing, combing, carding and spinning the yarn, to weaving and finishing the fine worsted for which the town was famous.

Of the 51 Heads of Household who left Swaledale for the West Riding between 1881 and 1891, forty-four households - 323 people - came to Haworth. In 1881, the average age of those 323 people was just 16 - an awful lot of young children accompanied their parents and most of them were working in the mills by 1891.

Of the forty-four heads of households, thirty-one had been miners. Six families left Booze, in Arkengarthdale, six left Blades, at Low Row, ten left Reeth. And they came to live in the noisy and tightly-packed streets of new, gas-lit, terrace housing, some of it back-to-back, near the mills. The streets had incongruous names: Jay, Lark, Wren, Dean, Lord, Regent, Prince. Earl. Victoria, of course. Some of it must have seemed wonderful. Some of it must have been almost intolerable.

Of the forty-four heads of households, thirty-one had been miners. Six families left Booze, in Arkengarthdale, six left Blades, at Low Row, ten left Reeth. And they came to live in the noisy and tightly-packed streets of new, gas-lit, terrace housing, some of it back-to-back, near the mills. The streets had incongruous names: Jay, Lark, Wren, Dean, Lord, Regent, Prince. Earl. Victoria, of course. Some of it must have seemed wonderful. Some of it must have been almost intolerable.

This is Prince Street Backs - clearly a better class of housing, although some houses were multi-occupancy. Hannah Metcalfe of Town End Farm, Reeth, lodged at No 23 Prince Street, a worsted weaver and a tenant of the Pickles family (yes - of Wilfred Pickles fame - I can just about remember his radio programmes in the 1950s). At the time of the 1891 census her sister Margaret was visiting her [Town End Farm had been the family home of Ed Tiplady, before his sorry decline - don't these names keep cropping up?]. Sergeant McLaren, whose wife Eliza had waited so patiently in Reeth, moved his family to Earl Street when he retired. All five of his now teenage children worked in the nearby woollen mills.