Telephone Week at the London Trunk Exchange

WHEN the Postmaster-General announced that after 7 p.m. Trunk calls could be made to any part of the British Isles for 1/-, it was evident that a great increase in evening traffic would result, especially in view of the wide publicity given to the telephone service during Telephone Week. The difference then existing between the evening conditions and the morning "busy-hour" was, however, so great that a sufficient margin of safety appeared to exist, and, so far as the London Engineering District was concerned, it was felt that the chief effect of the reduction in charges would be to prevent evening routine testing of repeatered circuits, and to necessitate an extension of the exchange maintenance staff rota to twenty-four hours.

It soon became evident on Monday, 1st October, that the reduced and uniform charge was appreciated by the public even beyond anticipation, for shortly after 7 p.m. the switchboard was ablaze with light as subscribers competed with each other to obtain their "shilling's worth". This condition is clearly seen in Fig. 1,  which represents the discharge current of the Trunk Exchange battery. Bearing in mind that this curve includes current supplied to the International Exchange, which did not participate in the evening rush of traffic, it is evident that the Inland Trunk Exchange had to face the sudden application of a load equal to, if not exceeding, that during the busiest period of the morning. Before this deluge of calls, of which a large proportion was confined to the long distance routes, the Demand System had, perforce, to give way to Delay Working.

which represents the discharge current of the Trunk Exchange battery. Bearing in mind that this curve includes current supplied to the International Exchange, which did not participate in the evening rush of traffic, it is evident that the Inland Trunk Exchange had to face the sudden application of a load equal to, if not exceeding, that during the busiest period of the morning. Before this deluge of calls, of which a large proportion was confined to the long distance routes, the Demand System had, perforce, to give way to Delay Working.

Strenuous efforts were made by the Traffic Staff to deal with the new conditions, but that, as Kipling would say, is another story, the object of these notes being merely to record the part played by the London Engineering District in meeting the emergency. The immediate cry was for more lines, more lines at once, and to meet this need aerial reserves, experimental circuits, in fact all lines over which reasonable transmission could be obtained, were commandeered. The transmission aspect was important, as the public are now accustomed to a high standard. To have rushed in low grade circuits would have been sheer waste of time and would only have given rise to complaints.

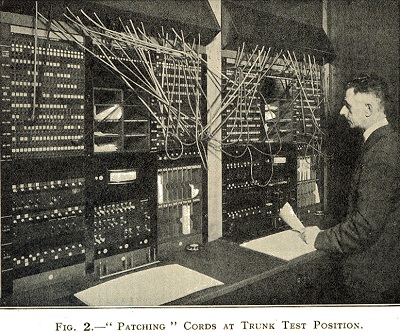

Obtaining the circuits was, however, only half the battle - there still remained the difficulty of connecting them to the switchboards, so that they could be used for traffic. For inland calls, the London Trunk Exchange consists of no less than 305 positions, situated in four different rooms, each room being provided with a separate multiple. To connect the new circuits at the end of the normal groups in these multiples meant joining up relay-sets, one of which is necessary at each end of a trunk circuit under the sleeve control system, jumpering to the various multiples, modifying the Visual Idle Indicating Equipment and altering the labels. Also, in cases where sufficient spare jacks did not exist at the end of the normal group, other groups of circuits had to moved to make room. All this work needed time, and time was precious, since the new circuits had to be ready for the rush of traffic anticipated on the following evening. Difficulties, however, are made to be overcome and the solution of this one lay in connecting a number of jacks over the Straightforward Junction Positions to relay-sets jumpered to the Trunk Test. These terminations formed a "pool" to which each new circuit was "patched" immediately it became available. Since every operator has access to the straightforward junction positions, the new circuits were available to all with an absolute minimum of delay.

To obtain additional lines, the L.T.S. arranged with the renters of private wires to release them for traffic purposes in the evening. These circuits also were "patched" into the pool by cords at the Trunk Test Position, which, as can be seen from Fig. 2,

ultimately resembled the after-math of a severe snowstorm in the old days of the aerial Trunk system. As a result of these efforts, no fewer than 28 long distance trunk circuits were available for traffic within twenty-four hours.

ultimately resembled the after-math of a severe snowstorm in the old days of the aerial Trunk system. As a result of these efforts, no fewer than 28 long distance trunk circuits were available for traffic within twenty-four hours.

On Tuesday evening the traffic was even heavier than on Monday, and, although the efforts which had been made enabled the completed calls to rise from 67.5% to 74% of the total bookings, it was evident that the new conditions were not a mere flash in the pan, and that the efforts to provide additional plant must be pushed on at high pressure.

More and more circuits were obtained from spare wires and connected to the pool, while, simultaneously, the work of transferring circuits from the pool to their proper allocations proceeded as rapidly as possible. All manner of devices were employed by the Engineer-in-Chief to produce additional circuits. For example, an additional London-Edinburgh circuit was obtained by using the Radio Termination-Cupar Speaker between London and Edinburgh during the times when it was not actually needed for radio purposes. Probably the most valuable assistance on the Scottish route was, however, obtained by stopping the reconditioning work on the old London-Birmingham Telegraph Cable (TS-BM No. 1). Joints were hastily remade and, by inserting 2-wire repeaters at Fenny Stratford, it was possible to provide seven London to Birmingham Trunks, which were used to release a similar number of 4-wire circuits for extension northwards. Incidentally, to save time, spare cable pairs were used to balance these repeaters, the artificial balancing network being constructed afterwards. The 4-wire circuits so released were extended by spare cable pairs from Birmingham to Leeds, and thence the circuits were taken through Newcastle to Edinburgh on 100 lb. and 150 lb. unloaded conductors in an old cable which was being reconditioned. The reconditioning was stopped and improvised arrangements were used to make the cable suitable for telephonic purposes, with the result that, by Friday evening, two London-Edinburgh circuits were available, and by the following day four more circuits to Edinburgh, and one to Aberdeen, were completed. The speed with which these circuits were set up is surely a record in long line provision.

By the end of the week, a total of 80 additional long distance Trunk circuits had been provided, representing an increase of 15% on the long distance routes connected to Trunk Exchange. In fact, it may fairly be claimed that a whole year's provision of long distance circuits had been provided in a single week, the total route mileage involved being approximately 20,000 miles. The circuits had all been connected in their proper groups in the multiples, except in the Provincial Exchange, where an extension of the multiple had just been completed and where a complete rearrangement was necessary. In addition, the part-time circuits (Private Wires, Telex Circuits, etc.) had been connected on the Trunk Test Desk to the "break jack" scheme, permitting their being taken into use for traffic purposes simply by moving insulating pegs and thus avoiding a multiplicity of "patching" cords.

So far reference has been made only to outgoing traffic, but rapid and effective action was also taken to facilitate the arrival of calls incoming at the Trunk Exchange from the subscribers in the London District, and also from other Group Centres endeavouring to call London subscribers or to use London as a switching centre.

Congestion occurred on local junctions from London Exchanges to Trunks, particularly on the Tandem-Trunk route. Immediate steps were taken to provide the additional junctions necessary, and these were completed by Wednesday evening. Congestion also occurred on the incoming Trunk positions, and by Thursday eight demand positions had been made into incoming positions by cross-connecting the incoming Trunk Multiple. A larger number of demand positions could not be released for this purpose, and some other method of relieving the incoming traffic at Trunk Exchange was necessary. This was obtained by making use of the Toll "A" and Toll "B" Exchanges. In many cases Group or Zone centres are connected to Toll "B" Exchange by lines of good transmission value, which are normally used for completing calls to subscribers within the London 10-mile circle. It was arranged that in such cases the traffic to subscribers in the whole of the London Toll Area should be routed over these lines, and. passed from Toll "B" to Toll "A" Exchange for completion via the Toll "A" Multiple. 40 additional Toll "B"-Toll "A" junctions were run in to permit this to be done, and, as a result, over 1000 calls each night were completed by this route. In all, 103 additional junctions had been provided by the 8th October.

Thus terminated a week's work by the Engineering Staff at the London Trunk Exchange, a week's work surely never equalled in the past, and unlikely to be surpassed in the future, work which could only have been done with the active co-operation of all Departments concerned and the loyal assistance of a staff which knew its job, and which, by virtue of the experience of snow-storms and cable breakdowns in the past, has learnt to work quickly and smoothly in an emergency.

F.I.R.

The Post Office Electrical Engineers' Journal, January 1935